Mafic Rocks are fundamental building blocks of our planet, especially when it comes to the igneous oceanic crust. These dark-colored, dense rocks, rich in minerals like pyroxene and plagioclase feldspar, are constantly being formed at mid-ocean ridge seafloor spreading centers. This creation process, a result of partial melting of the Earth’s upwelling mantle, gives rise to vast expanses of mafic crust beneath the oceans. But beyond their composition and origin, a critical property of mafic rocks in this environment is their permeability – their capacity to allow fluids to flow through them. Understanding the permeability of mafic rocks in the oceanic crust is vital, not just for comprehending the fundamental geology of our planet but also for its far-reaching implications, from economic mineral deposits to the very dynamics of plate tectonics, volcanic activity, and even earthquakes.

The Genesis of Permeability in Mafic Oceanic Crust

The journey of mafic rocks from molten mantle to solid crust is intrinsically linked to the development of permeability. As new oceanic crust forms at mid-ocean ridges, both intrusive gabbros and extrusive basalts – key types of mafic rocks – undergo processes that generate pathways for fluid flow. Extensional faulting, a dominant tectonic force at spreading centers, creates a network of interconnected fractures deep within the crust. Nearer to the surface, rapid cooling (quenching) of lava, degassing, ongoing faulting, and the very nature of lava flows contribute to the formation of breccia, talus slopes, and other rubble-like structures, especially in the upper few hundred meters of the crustal section. These geological features dramatically enhance the porosity and consequently the permeability of the mafic rock formations.

This enhanced permeability becomes the engine for ventilated hydrothermal convection at ridge crests and flanks. Cold seawater is drawn into the newly formed, hot mafic rocks, circulating through the fracture networks. This circulation isn’t just a passive process; the influx of cold seawater further promotes fracture development through thermal contraction, essentially widening and deepening the pathways for fluid flow within the mafic rocks.

Figure 1. (a) This image illustrates the location of a geophysical transect, marked by a dashed line, which is the focus of the study discussed in the article. It also shows the broader tectonic setting in the inset. Solid circles indicate the positions of Ocean Drilling Program (ODP) boreholes. The triangles in the inset represent active volcanoes in the region. (b) A cross-section view along the transect, displaying the topography of the seafloor and basement, as well as the locations of boreholes and heat flow measurement sites.

Eventually, as the oceanic crust ages and moves away from the ridge, sediment deposition begins to blanket the mafic rocks, effectively capping and limiting the direct ventilation with seawater. However, hydrothermal convection does not cease. It persists within the sediment-buried igneous rocks, continuing to circulate until the permeability is gradually reduced over geological timescales by the precipitation of minerals that fill the open spaces and fractures. Interestingly, the permeability of older oceanic crust, composed of these mafic rocks, isn’t static. Tectonic events, such as normal faulting and the bending (flexure) of the crust as it approaches subduction zones, can rejuvenate permeability, reopening fractures and creating new pathways for fluid flow.

Why Permeability of Mafic Rocks Matters: From Mineralization to Plate Tectonics

The permeability of mafic rocks in the oceanic crust is far from an academic curiosity. It has profound implications across a range of Earth science disciplines. Firstly, understanding this permeability is critical for understanding economic mineral deposition. Hydrothermal circulation, driven by permeability within mafic rocks, is responsible for concentrating valuable minerals in certain oceanic crust environments.

More broadly, the permeability of oceanic crust, predominantly composed of mafic rocks, plays a crucial role in plate tectonics. Newly formed oceanic crust at mid-ocean ridges is initially considered “dry,” meaning the high temperatures and pressures prevent the formation of hydrous minerals, except in the very shallow, rapidly cooled surface. However, as this crust ages and interacts with seawater through permeable pathways, it becomes “wet.” Significant amounts of water become incorporated into the mafic rocks, bound within hydrous alteration minerals formed as seawater penetrates and reacts with the rock matrix at various depths.

As oceanic plates, laden with hydrated mafic rocks, descend into subduction zones, the increasing pressure and temperature trigger metamorphic transformations. Basalt and gabbro, the mafic components, convert into denser eclogite. Crucially, this metamorphic process involves dehydration – the release of the water that was trapped in the hydrous minerals within the altered mafic rocks. This dehydration process is a key driver of volcanic arcs above subduction zones and is also implicated in the generation of earthquakes within the subducting crust. Furthermore, dehydration of serpentine, a mineral formed by hydration of the upper mantle, is also proposed as a cause of earthquakes in the subducted oceanic mantle, suggesting that fluid circulation, enabled by permeability, can extend deep below the crust.

Figure 2. (a) This graph presents heat flow measurements, marked as dots, taken along the geophysical profile illustrated in Figure 1b. The curves shown on the graph represent model-predicted values, which are further discussed in Section 2 of the original article. (b) A cross-section view along the same profile, providing a visual representation of the subsurface geological structure.

The amount of water that enters the oceanic crust and upper mantle, and the depth to which it penetrates, are directly controlled by the permeability structure of the mafic rocks. Therefore, deciphering this permeability is essential for understanding the global water cycle and the deep Earth processes that shape our planet.

Measuring Permeability in Mafic Oceanic Crust: Diverse Approaches

Estimating the permeability of mafic oceanic crust is not a straightforward task due to the vast scales and depths involved. However, scientists have developed ingenious methods to probe this hidden property. Studies conducted at the Juan de Fuca Ridge and its eastern flank provide excellent examples of how permeability estimates are derived in young oceanic crust. This region, a divergent plate boundary between the Pacific and Juan de Fuca plates, is where new mafic-rich crust is formed at an intermediate spreading rate. The eastern flank of this ridge is eventually subducted beneath the North American plate at the Cascadia subduction zone, making it a critical area for studying the processes described above.

Researchers utilize a range of measurements to constrain permeability, including:

Heat Flow Measurements: Detailed heat flow measurements across the seafloor provide insights into convective heat transport, which is directly influenced by permeability. Higher permeability allows for more efficient convective heat transfer, leading to characteristic patterns in seafloor heat flow. By analyzing these patterns and comparing them to thermal models, scientists can infer the bulk permeability of the underlying mafic rocks.

Borehole Temperature and Pressure Monitoring: The Ocean Drilling Program (ODP) has been instrumental in deploying sophisticated instruments in boreholes drilled into the oceanic crust. CORKs (Circulation Obviation Retrofit Kits) are বিশেষভাবে designed borehole seals that allow for long-term monitoring of temperature and fluid pressure within the formation. Pressure sensors, placed both at the seafloor and within the sealed borehole, record pressure variations.

Formation fluid pressure records.

Formation fluid pressure records.

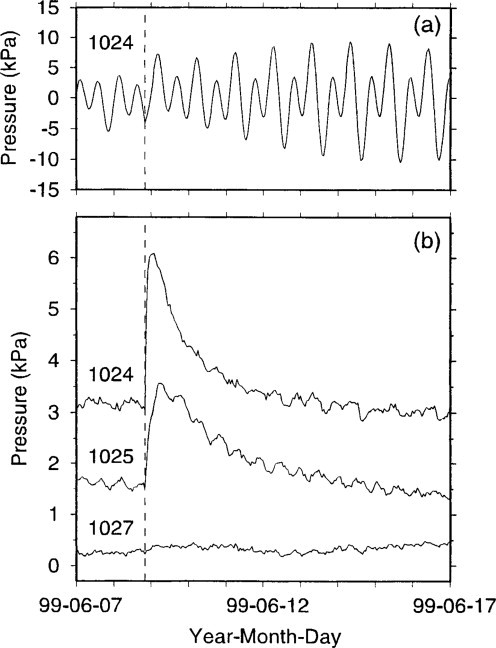

Figure 3. This figure shows examples of formation fluid pressure records collected from Ocean Drilling Program (ODP) boreholes. (a) Presents raw data from ODP hole 1024C, recorded between June 7-17, 1999. The dominant pressure signal is due to lunar and solar ocean tides. The implications of these tidal signals are discussed further in Section 3 of the original article. (b) Displays pressure records from holes 1024C, 1025C, and 1027C during the same period, but with the tidal signals removed. These records reveal pressure disturbances caused by a tectonic strain event on June 8, 1999. The tectonic pressure variations are discussed in Section 4 of the original article.

Analyzing pressure signals provides several avenues for permeability estimation:

- Formation Pressure Equilibration: After a borehole is sealed with a CORK, the pressure within the borehole gradually adjusts to reach the formation pressure. The rate of this pressure equilibration is related to the permeability of the surrounding mafic rocks.

- Tidal Pressure Signals: Oceanic and Earth tides induce pressure variations in the crust. The amplitude and phase shift of the pressure response in the borehole, compared to seafloor tidal pressure, are sensitive to formation permeability.

- Tectonic Pressure Signals: Seismic or aseismic faulting events generate strain pulses that cause sudden pressure changes in the formation fluid. The way these pressure disturbances propagate and dissipate provides information about the crustal permeability.

By carefully analyzing these diverse datasets – heat flow, borehole temperatures, and pressure responses to tidal and tectonic forces – scientists can build a comprehensive understanding of the permeability structure of mafic oceanic crust.

The Scale Dependence of Permeability in Mafic Rocks

It’s crucial to recognize that permeability is not a fixed property of mafic rocks; it depends significantly on the scale at which it is measured. At the microscopic scale of a small, unfractured sample of basalt, permeability is virtually negligible. Measurements on core samples in the laboratory typically yield very low permeability values. However, when permeability is assessed at larger scales, such as around a borehole, or across tens of kilometers of oceanic crust, the values are typically much higher.

This scale dependence reflects the hierarchical nature of permeability in mafic rocks. Small-scale permeability is dominated by the intrinsic porosity of the rock matrix itself. At larger scales, permeability is increasingly controlled by fractures, faults, and other larger-scale geological features that act as preferential pathways for fluid flow. The “formation permeability” measured through methods like heat flow analysis and multi-borehole pressure monitoring represents the effective permeability at a large scale, encompassing the contributions of these interconnected fracture networks.

While at very large scales, treating the fractured mafic rock formation as a uniform porous medium might be a simplification, the concept of formation permeability remains invaluable. It allows scientists to quantify the average hydrologic characteristics of these highly permeable geological formations and to predict fluid flow at regional scales. Just as “effective elastic thickness” is used to describe the overall flexural strength of the lithosphere, formation permeability provides a meaningful way to characterize the bulk fluid transport properties of mafic oceanic crust, essential for understanding hydrothermal circulation, geochemical transport, and the deep Earth water cycle.

References

- Clauser, C., 1992. Permeability of crystalline rocks. Surveys in Geophysics, 13(3), pp.163-221.

- Davis, E.E., Becker, K.,橋本, J., Fulton, P.M. and Wilcock, W.S.D., 2001. Permeability of young oceanic crust and implications for thermal models. Geophysical Journal International, 144(1), pp.123-146.

- Davis, E.E., Chapman, D.S., Forster, C.B., Gable, R., Gerlach, D.C., GREGORY, R.T., 이어, J.H., Lister, C.R.B., Louden, K.E., Moore, J.C. and Mottl, M.J., 1992. CORK: a hydrologic seal and downhole observatory for deep-ocean boreholes. In Proc. Ocean Drill. Program, Init. Repts (Vol. 139, pp. 43-53).

- Fisher, A.T., 1998. Permeability within basaltic oceanic crust. Reviews of Geophysics, 36(2), pp.143-182.

- Giambalvo, E.R., Fisher, A.T., मार्टिन, E.E. and Wheat, C.G., 2000. Geochemical evidence for ridge-flank hydrothermal circulation at Baby Bare outcrop, Juan de Fuca Ridge eastern flank. Journal of Geophysical Research: Solid Earth, 105(B7), pp.16745-16762.

- Kirby, S.H., Engdahl, E.R. and Denlinger, R.P., 1996. Limits on depth to faulting at circum‐Pacific subduction zones: Implications for mantle phase‐change models. Journal of Geophysical Research: Solid Earth, 101(B3), pp.5517-5532.

- Peacock, S.M., 2001. Are the lower planes of double seismic zones caused by serpentine dehydration in subducting oceanic mantle?. Geology, 29(4), pp.299-302.

- Peacock, S.M. and Wang, K., 1999. Seismic consequences of warm versus cool subduction metamorphism: examples from southwest and northeast Japan. Science, 286(5448), pp.2309-2313.

- Snelgrove, S. and Forster, C.B., 1996. Analysis of advective fluxes and hydraulic properties in a layered sediment sequence in the eastern flank of the Juan de Fuca Ridge. Earth and Planetary Science Letters, 144(1-2), pp.139-156.