As content creators for rockscapes.net, we’re immersed in the world of rocks daily. But have you ever stopped to ponder a seemingly simple question: what exactly is the difference between a rock and a stone? This question, seemingly straightforward, actually unearths a fascinating journey into language, geology, and even popular culture. Like many who delve into urban geology and the stories hidden within our cityscapes, the distinction between “rock” and “stone” has become a captivating puzzle.

Delving into this topic, initial online searches reveal a variety of folk wisdom. Some suggest “stone” is more British, others propose rocks can be soft while stones are always hard. Further down the rabbit hole, you might find theories that stones are smooth and rocks are rough, or that size dictates the term – stones being small and rocks being large. However, to truly understand the subtle divide, we need to dig a little deeper, much like a geologist unearthing the secrets of the Earth.

Dictionary Definitions: The Weight of Words

To gain a more authoritative perspective on “Rock And Stone”, we turn to the venerable Oxford English Dictionary (OED). The OED defines rock first and foremost as “A large rugged mass of hard mineral material or stone.” Interestingly, the earliest recorded use of “rock” dates back to Old English, between 950-1100. Conversely, stone is defined as “A piece of rock or hard mineral substance of a small or moderate size,” with its first recorded usage in 825. This initial foray into etymology suggests that size might indeed play a role, with “stone” implying a smaller, more manageable piece of “rock”.

Adding another layer of intrigue, the OED reveals the word stonerock, defined as “A pointed or projecting rock, a peak, a crag; a detached mass of rock, a boulder or large stone,” actually predates both “stone” and “rock” individually. “Stonerock,” or stanrocces from Early Old English (600 to 950), existed before the separate terms became common. While this doesn’t definitively solve our rock and stone conundrum, it highlights the long and intertwined history of these words in the English language. The sheer volume of definitions in the OED – three pages for “rock” and four and a half for “stone,” filled with fascinating compounds like “rock nosing” and “stone harmonicon” – underscores the richness and complexity embedded within these seemingly simple terms.

Biblical and Shakespearean Insights: Words Through the Ages

Venturing beyond dictionaries, we can explore how “rock and stone” have been used in influential texts. The King James Bible, for example, often employs “stone” and “rock” seemingly interchangeably. Genesis 31:46 recounts Jacob instructing his brethren to “Gather stones; and they took stones, and made an heap.” Yet, a closer look reveals subtle distinctions even in this ancient text.

Consider the phrase “stone them with stones,” appearing numerous times in the Bible. While grammatically you could say “stone them with rocks,” the phrase “rock them with rocks” simply doesn’t resonate in the same way. This highlights a nuance – “stone” in this context feels more readily weaponized, perhaps due to its manageable size. In contrast, the Bible frequently uses “rock” metaphorically to represent something solid and foundational, particularly as “the rock of one’s salvation.” This metaphorical “rock” embodies strength, stability, and unwavering faith – qualities not typically associated with a smaller “stone.” No one refers to the “stone of salvation,” reinforcing the idea that “rock” carries a connotation of greater size and significance in this context.

Shakespeare, another literary giant, also utilized “stone and rock” extensively in his works. He employed “stone” over 115 times and “rock” more than 50 times. In As You Like It, the banished Duke famously proclaims, “Sermons in stones and good in every thing.” Here, Shakespeare’s choice of “stone” likely stems from alliteration and sound, as further exemplified in Titus Andronicus: “A stone is soft as wax,—tribunes more hard than stones; A stone is silent, and offendeth not.” The “insolent quietness of stone,” as poet Robinson Jeffers described it, further captures this sense of stillness and perhaps smaller scale.

Shakespeare’s use of “rock,” however, often takes on a more formidable and maritime association. Phrases like “Rocks threaten us with wreck,” “the peril of waters, winds and rocks,” and “the sea hath cast me on the rocks” evoke images of massive, dangerous formations. Substituting “stone” in these nautical contexts diminishes the sense of overwhelming, immovable danger that “rock” conveys. Again, Shakespeare’s word choice reinforces the idea of “rock” as something large, imposing, and potentially threatening.

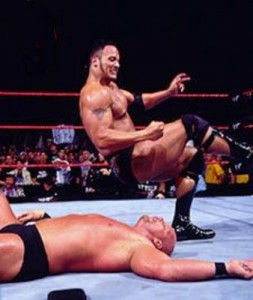

Pop Culture Perspectives: The Rock vs. Stone Cold

To further illustrate the perceived differences between “rock and stone”, we can turn to the realm of popular culture, specifically the world of professional wrestling. Consider the iconic personas of “The Rock” and “Stone Cold” Steve Austin. These two figures, larger-than-life in their respective domains, embody the subtle distinctions we’ve been exploring. “The Rock” suggests something monumental, a force of nature, an immovable object. “Stone Cold,” while still conveying toughness, perhaps implies a more grounded, less overtly massive presence. Whether intentional or not, these wrestling monikers playfully tap into the nuanced connotations of “rock and stone.”

Concluding Thoughts: Navigating the “Rock and Stone” Landscape

Ultimately, after exploring dictionary definitions, literary examples, and even pop culture references, we arrive at a nuanced understanding of “rock and stone.” There is a subtle difference, albeit often blurred in everyday language. Robert Thorson’s insightful observation that “Stone usually connotes either human handling or human use” resonates strongly. “Stone” often implies a piece of rock that is smaller, more easily manipulated, and frequently utilized by humans – think of building stones, paving stones, or even a skipping stone.

“Rock,” on the other hand, tends to encompass larger formations, geological masses, and metaphorical foundations. While “stone” can certainly be hard, “rock” emphasizes solidity, immovability, and grandeur. In essence, while all rocks can be considered stones, not all stones rise to the scale and significance of being called “rocks.” The distinction, like many aspects of geology and language, is not always clear-cut, but understanding these subtle shades of meaning enriches our appreciation for both the words we use and the earth beneath our feet. So, the next time you encounter a geological feature, take a moment to consider: is it a rock, or is it a stone? And what subtle story does that word choice tell?