Clastic Sedimentary Rocks are a fundamental category in geology, forming a significant portion of the Earth’s surface and holding valuable clues to our planet’s history. As content creators at rockscapes.net, we aim to provide you with an in-depth understanding of these fascinating rocks. This guide expands upon the basics, offering a comprehensive exploration of clastic sedimentary rocks, their formation, classification, and significance.

Understanding Clasts: The Building Blocks

The term “clastic” itself comes from the Greek word “klastos,” meaning broken. This aptly describes the nature of clastic sedimentary rocks, which are composed of fragments, or clasts, of pre-existing rocks and minerals. These clasts vary dramatically in size, from microscopic clay particles to massive boulders larger than houses.

As explored in previous discussions on weathering, quartz is a common constituent of sand-sized clasts due to its exceptional resistance to weathering processes. Smaller clasts are often fragments of rocks like basalt or andesite, while larger clasts can originate from coarse-grained rocks such as granite or gneiss. Figure 1 illustrates the diversity in clast types.

Variety of sediment clasts including different rock and mineral fragments

Variety of sediment clasts including different rock and mineral fragments

Grain Size: The Udden-Wentworth Scale

To effectively study and categorize sediments and sedimentary rocks, geologists employ the Udden-Wentworth grain-size scale. This standardized scale provides a systematic way to describe the size of grains within these materials (Table 1).

Table 1: The Udden-Wentworth Grain-Size Scale

| Description | Size Range (mm) | Size Range (microns) |

|---|---|---|

| Boulder | >256 | >256,000 |

| Cobble | 64-256 | 64,000-256,000 |

| Pebble/Granule | 2-64 | 2,000-64,000 |

| Sand | 0.063-2 | 63-2,000 |

| Silt | 0.004-0.063 | 4-63 |

| Clay | <0.004 | <4 |

The Udden-Wentworth scale divides grain sizes into categories like boulders, cobbles, pebbles, sand, silt, and clay. Notice the logarithmic nature of the scale; each category limit is twice the size of the one below it. This reflects the natural distribution of sediment sizes and allows for a practical classification system.

Imagine the difference in size: a boulder can be larger than a toaster, while clay particles are microscopic. Sand, with its characteristic gritty feel, ranges from 2 mm down to 0.063 mm. Silt, finer than sand, feels smooth but gritty in your mouth. Clay, the finest fraction, is smooth even to the taste.

Sediment Settling: Gravity vs. Friction

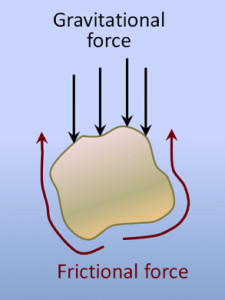

If you were to drop different sized grains into water, you’d observe varying settling rates. A granule sinks rapidly, sand takes a bit longer, silt settles more slowly, and clay particles may remain suspended indefinitely. This is due to the interplay of gravity and friction (Figure 2).

Diagram illustrating gravity and friction forces on a sediment grain settling in water

Diagram illustrating gravity and friction forces on a sediment grain settling in water

Larger particles settle faster because gravity, proportional to volume, outweighs friction, proportional to surface area. For smaller particles, the difference is less pronounced, leading to slower settling.

Transportation of Clasts: The Role of Flow Velocity

A key principle in sedimentary geology is that a moving medium’s (water, air, ice) ability to transport particles depends on its velocity. Higher velocity means larger particles can be moved. Think of a river: faster currents can carry boulders, while slow-moving sections might only transport fine silt and clay (Figure 3).

River scene showing variations in flow velocity and sediment transport

River scene showing variations in flow velocity and sediment transport

Rivers aren’t uniform; velocity changes with slope, channel width, and discharge (water volume per time). During floods (peak discharge), rivers gain energy to move even large boulders.

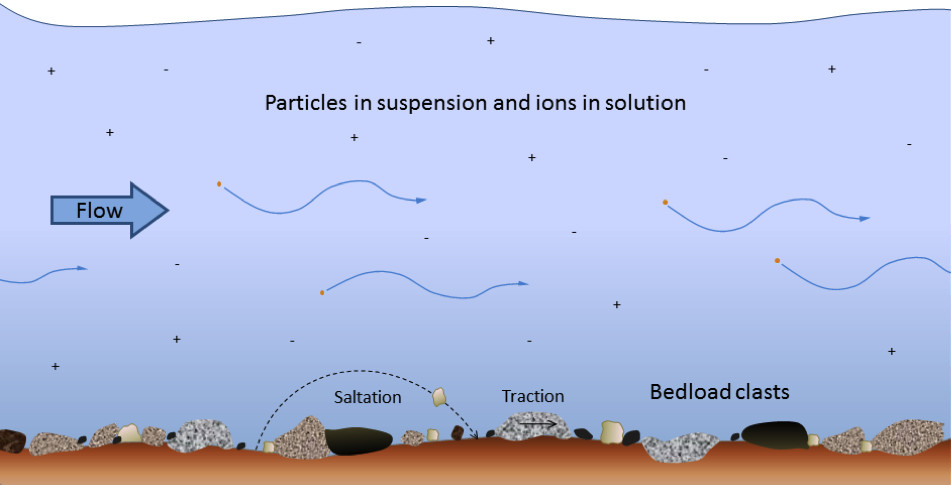

Clasts in streams are transported in several ways (Figure 4):

- Traction: Larger bedload clasts are pushed or rolled along the riverbed.

- Saltation: Medium-sized clasts bounce along the bottom.

- Suspension: Smaller clasts are kept aloft by water turbulence.

- Solution: Dissolved ions are transported within the water itself.

Diagram showing different modes of sediment transport in a stream

Diagram showing different modes of sediment transport in a stream

Similar principles apply to other transport agents like waves, ocean currents, and wind. Velocity is the primary control on sediment transportation and deposition.

Lithification: From Sediment to Solid Rock

Lithification is the process that transforms loose sediment into solid sedimentary rock. Key processes include:

- Compaction: Burial by overlying sediments compresses the material, reducing pore space and squeezing out water and air. Clasts become tightly packed.

- Cementation: Minerals precipitate from groundwater and crystallize in the pore spaces between clasts. Common cements include calcite, quartz, and iron oxides, binding the clasts together.

- Crystallization: In some cases, minerals may directly crystallize within the sediment matrix, further solidifying the rock.

Types of Clastic Sedimentary Rocks

Clastic sedimentary rocks are categorized primarily by their dominant clast size and composition (Table 2).

Table 2: Main Types of Clastic Sedimentary Rocks

| Group | Examples | Characteristics |

|---|---|---|

| Mudrock | Mudstone, Shale | >75% silt and clay-sized particles |

| Sandstone | Quartz Arenite, Arkose, Lithic Wacke | Dominated by sand-sized grains |

| Conglomerate | Conglomerate | Rounded, pebble-sized or larger clasts |

| Breccia | Breccia | Angular, pebble-sized or larger clasts |

| Coal | Coal | Composed of compacted plant matter |

Mudrocks: The Fine-Grained Sediments

Mudrocks are composed of at least 75% silt and clay. Claystone is dominated by clay, while shale is mudrock exhibiting bedding or fine laminations. Mudrocks form in low-energy environments like lakes, deep oceans, and floodplains where fine particles can settle.

Sandstones: A World of Variety

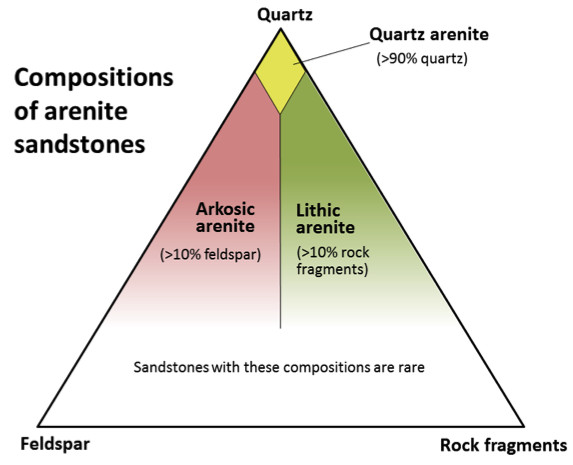

Sandstones are defined by their sand-sized dominance. Arenites are “clean” sandstones with less than 15% silt and clay matrix. Within arenites:

- Quartz Arenites: >90% quartz grains; very mature sandstones often from beaches or deserts.

- Arkose (Feldspathic Arenites): >10% feldspar; indicate less weathering and closer proximity to source rocks.

- Lithic Arenites: >10% rock fragments; also indicate less weathering and diverse source rocks.

Wackes (or greywackes) are sandstones with more than 15% silt and clay matrix. They are less “clean” and often form in rapidly deposited environments. Figure 5 illustrates sandstone composition.

Compositional triangle for arenite sandstones

Compositional triangle for arenite sandstones

Figure 6 shows microscopic views of different sandstone types, highlighting their textural and compositional variations.

Microscopic images of quartz arenite, arkose, and lithic wacke sandstones

Microscopic images of quartz arenite, arkose, and lithic wacke sandstones

Conglomerates and Breccias: The Coarse Clastics

Conglomerates and breccias are coarse-grained clastic rocks with a significant proportion of clasts larger than 2 mm. The key difference lies in clast shape:

- Conglomerates: Composed of rounded clasts, indicating significant transport distance and abrasion, typically formed in river channels.

- Breccias: Composed of angular clasts, suggesting minimal transport, often formed in environments like alluvial fans or fault zones.

Coal: Organic Clastic Rock

Coal, while sometimes classified as an organic sedimentary rock, is included with clastics here because it’s made of fragmented plant matter and often interbedded with clastic rocks like mudstone and sandstone. Coal forms in swamp environments with low oxygen, where plant debris accumulates and undergoes compaction and coalification.

Importance and Applications

Clastic sedimentary rocks are economically and scientifically important. They:

- Contain groundwater aquifers: Porous sandstones can hold significant water resources.

- Host fossil fuels: Oil and natural gas often accumulate in porous sandstones and shales. Coal is a major energy source.

- Provide building materials: Sandstones and conglomerates are used in construction.

- Record Earth’s history: Clastic rocks preserve evidence of past environments, climates, and tectonic activity.

Conclusion

Clastic sedimentary rocks are diverse and informative archives of Earth’s processes. From microscopic clay to massive boulders, their clasts tell stories of weathering, erosion, transport, and deposition. Understanding their classification, formation, and characteristics provides crucial insights into geology, resource exploration, and environmental history. As you continue your exploration of rocks, remember the clastics – they are fundamental keys to unlocking the secrets of our planet.