The allure of unique geological wonders often draws travelers to explore the most fascinating corners of our planet. Among these captivating sites, the Pink Granite Coast in Brittany, France, stands out with its breathtaking landscapes sculpted from vibrantly hued Pink Rocks. This article delves into the geology behind these stunning pink formations, revealing the secrets of their color, shape, and the processes that have crafted this extraordinary coastal scenery.

croissant and rocks

croissant and rocks

The Brittany coast is a geological playground, and for enthusiasts of rocks and natural beauty, it’s an unparalleled destination. While granite is common in Brittany, the area around Trébeurden and Ploumanac’h is special. Here, the typical grey granite dramatically gives way to extensive stretches of strikingly pink rock. This transformation ignites curiosity: what geological story explains this vibrant color shift and the peculiar shapes of these pink rock formations?

IMG_20190716_190632806_HDR

IMG_20190716_190632806_HDR

IMG_20190716_193830844

IMG_20190716_193830844

The story of these pink rocks is one of geological threes – a trinity of factors contributing to their unique character. The pink granite is composed of three key minerals, formed during three distinct igneous events, and sculpted by three different erosional forces into the whimsical shapes we see today.

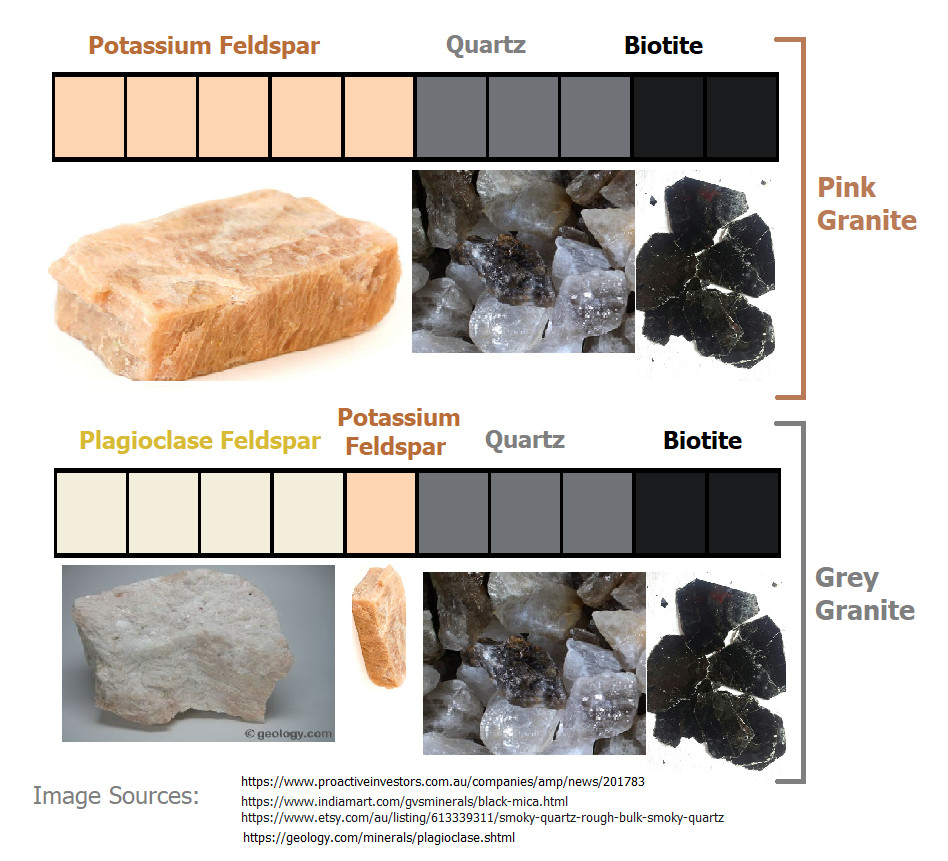

The distinctive pink hue of the granite originates from its mineral composition. Potassium feldspar is the mineral responsible for the rosy color, contrasting with grey granite which contains more plagioclase feldspar, giving it a creamier appearance. Pink granite is typically composed of approximately 50% potassium feldspar, 30% quartz, and 20% biotite. This mineral combination is what gives pink rock its signature shade.

Pink Grey Granite Comparison

Pink Grey Granite Comparison

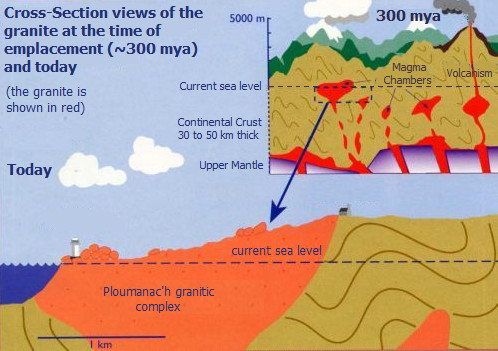

These pink and grey granites in Ploumanac’h were formed around 300 million years ago, during the final stages of a significant mountain-building period. This era saw the collision of the ancient continents Gondwana and Laurussia, culminating in the supercontinent Pangaea. Over vast geological timescales, erosion gradually exposed these buried granite masses, bringing them to the surface and shaping the landscapes we see today.

pink granite emplacement diagram.png

pink granite emplacement diagram.png

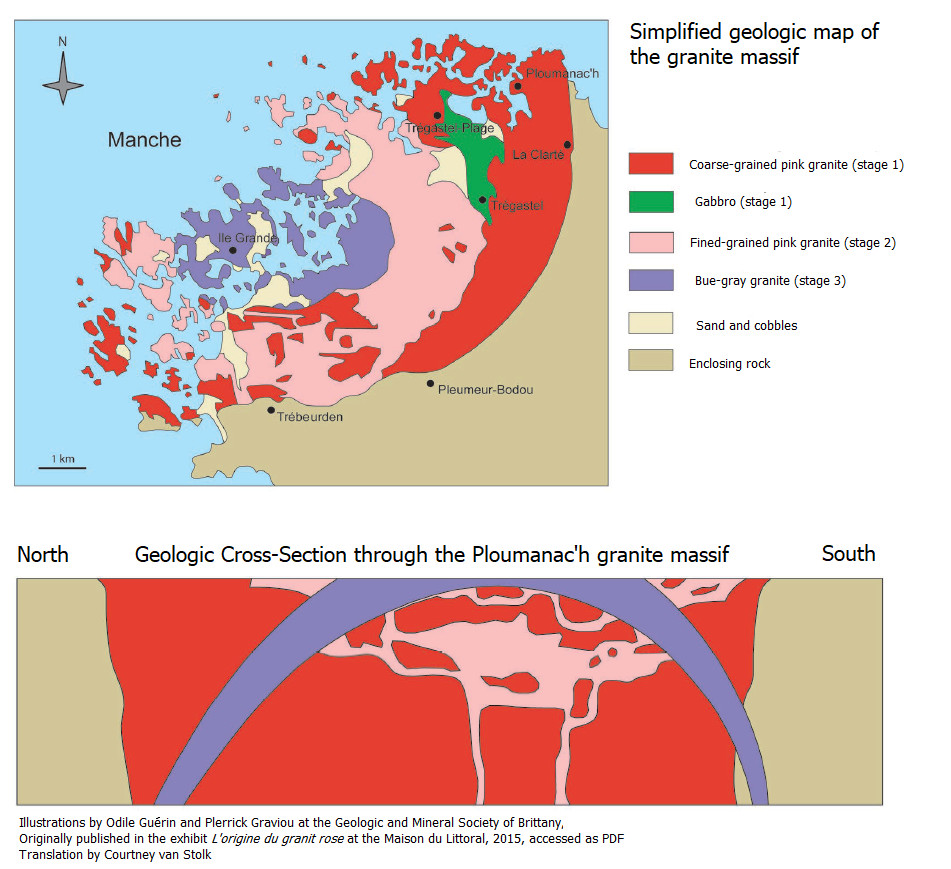

Delving deeper into the geological history, the granite formation occurred in three distinct phases around 300 million years ago. The first phase involved the simultaneous intrusion of two magma types into the existing metamorphic rock. One magma, rich in silicon, solidified into the coarse-grained pink granite, while the other, less silicon-rich, formed the dark gabbro found near Tregastel. These different magma compositions arose from the melting of distinct source rocks.

The second phase saw another silicon-rich magma penetrate fissures within the already solidified pink granite from the first phase. This subsequent magma, similar in composition to the first pink granite, cooled more rapidly, resulting in smaller mineral crystals.

Finally, in the third phase, a more basic magma intruded into a dome-shaped weakness in the granite formed in the previous two phases. This last magma cooled to form the blue-grey granite observable near Ile-Grande.

Pink granite massif geo map and cross section

Pink granite massif geo map and cross section

The variation in color between the pink rocks of Ploumanac’h, the grey granite at Trébeurden, and even the pale granite of Mont Saint-Michel (formed around 520 million years ago), is not merely aesthetic. These color differences reflect variations in mineral composition, providing geologists with valuable clues about the source rocks that melted to form these granites. The presence of feldspars and quartz, rich in silicon, indicates that the source rocks were abundant in silica.

Silica and oxygen combine to form a wide array of minerals, varying in density and silicon-oxygen ratios. Generally, less dense, silicon-rich minerals are more prevalent in the continental crust, while denser, silicon-poor minerals are more common in the oceanic crust.

The igneous rock classification chart illustrates these relationships between mineral properties and rock types. This chart helps geologists understand the likely origin of igneous rocks based on their mineral content. The pink granite, for example, indicates formation from low-density, high-silica rocks melting at relatively low temperatures.

The grey granite at Trébeurden, positioned slightly to the right on the chart, remains a granite but contains more minerals with higher melting points and less potassium feldspar. Gabbro, like that at St. Anne, is further to the right, suggesting formation from melted oceanic crust. The pale granite at Mont Saint-Michel likely originated from low-temperature melts (~600°C) or source rocks lacking the chemistry to form dark mica or amphibole crystals.

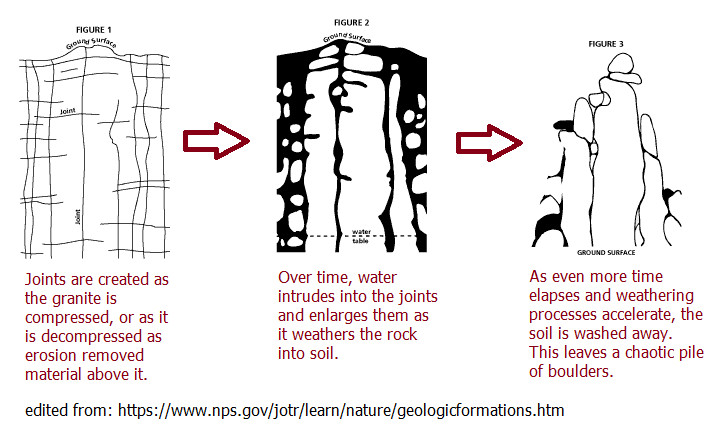

Beyond the captivating color, the extraordinary shapes of the pink rock formations are equally intriguing. Unlike boulders shaped by turbulent mountain streams, these pink rock boulders have remained largely in place since the granite cooled. Their unique forms are the result of in-situ erosion, a process eloquently termed “un chaos” in French, perfectly capturing the seemingly random yet beautifully ordered arrangement of these rocks.

granite chaos creation

granite chaos creation

The formation of this “chaos” is driven by changes in weathering and erosion rates. Initially, slow dissolution by groundwater sculpted the granite underground, pre-shaping the boulders. Later, as sea levels changed and the coastline evolved, more rapid erosion from wave action exposed these pre-formed boulders.

Once exposed, two slower forms of chemical erosion further refine the pink rocks into even more intricate shapes. Salt spray reacts with mica and feldspar crystals, transforming them into weaker clay minerals that are gradually washed away. This salt weathering creates characteristic divots and creases, especially in areas where salt accumulates.

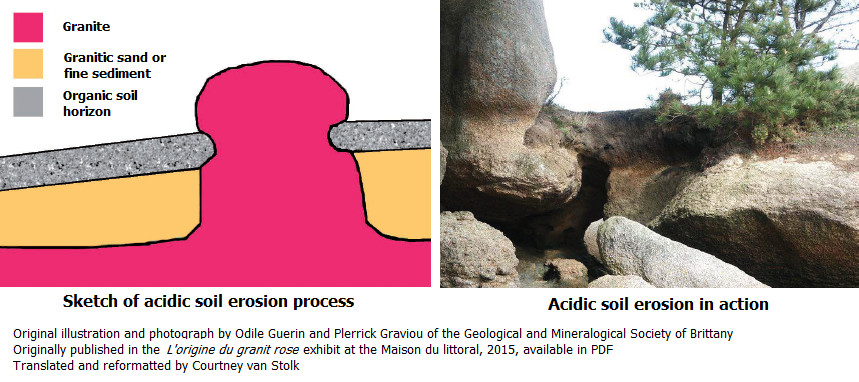

Simultaneously, organic acids in the soil at ground level slowly erode the base of the rocks over thousands of years, contributing to the development of subtle mushroom-like shapes.

acidic soil erosion

acidic soil erosion

The combination of these erosional forces has sculpted the Pink Granite Coast into a wonderland of geological art. Exploring this area is an unforgettable experience, offering a chance to witness the power of natural processes shaping our planet over millions of years.

Walking along the Pink Granite Coast, you can observe quartz veins within the pink rock and identify salt weathering divots, tangible evidence of the ongoing erosional processes.

pink granite castle

pink granite castle

Exploring the formations reveals hidden details, like salt-weathered “crow’s nests,” showcasing the intricate sculpting power of nature. The Pink Granite Coast is more than just a beautiful landscape; it’s a living geology lesson, inviting exploration and wonder at every turn.

Sources (all are in French):

Great summary from the local natural history museum, the Maison du littoral: http://ville.perros-guirec.com/fileadmin/user_upload/mediatheque/Ville/Maison_du_littoral/refonte_page_environnement/expo_origine_du_granit_roseBD.pdf

Less technical summary from the local tourist board: http://www.cotedegranitrose.net/la-cote-de-granit-rose/geologie-le-granit-rose/

Long and extremely thorough field trip guide published by the Geological and Mineralogical Society of Brittany: https://sgmb.univ-rennes1.fr/geotopes/decouvertes/23-decouvertes/67-ploumanac-h

Short summary/technical field trip guide: http://www.saga-geol.asso.fr/Geologie_page_conf_Ploumanach.html