True crime stories have surged in popularity, fueled by gripping dramas, insightful podcasts, and in-depth documentaries. This increased media attention has also shed light on critical issues within the justice system, notably the disturbing phenomenon of false or coerced confessions. There was a time when a confession, regardless of subsequent retractions or contradictory evidence, essentially sealed a defendant’s fate. However, contemporary understanding acknowledges the unsettling reality of individuals confessing to crimes they did not commit, often due to immense pressure, including threats of the death penalty by law enforcement. The decades-old case of the Starved Rock State Park Murders vividly illustrates this complex and troubling aspect of criminal justice.

In March 1960, the tranquility of Starved Rock State Park in Utica, Illinois, was shattered by the brutal murders of three women. Mildred Lindquist, Frances Murphy, and Lillian Oetting were visiting from Chicago when they were savagely killed. The crime sent shockwaves through the small town and quickly escalated into a national news sensation. Eight months later, Chester Weger, a 21-year-old dishwasher at the Starved Rock Lodge, confessed to the heinous acts. Despite recanting his confession before trial and maintaining his innocence ever since, Weger was convicted. After serving six decades behind bars, he was paroled at the age of 81, yet continues his unwavering quest to clear his name in a case that remains shrouded in doubt.

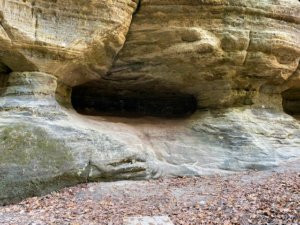

The Grisly Discovery at St. Louis Canyon

Entrance to St. Louis Canyon at Starved Rock State Park

Entrance to St. Louis Canyon at Starved Rock State Park

On March 14, 1960, Mildred Lindquist, 50, Frances Murphy, 47, and Lillian Oetting, 50, embarked on what should have been a relaxing four-day getaway to the scenic Starved Rock State Park near Utica, Illinois. After arriving at the Starved Rock Lodge and enjoying lunch, the women ventured into the picturesque St. Louis Canyon for a hike. Tragically, they would never return.

When the women failed to respond to calls on Monday evening and Tuesday morning, their families grew increasingly worried. A search party was organized on Wednesday morning, and within hours, the horrifying discovery was made. The women’s bloodied and battered bodies were found inside a secluded cave within St. Louis Canyon. They had been brutally bludgeoned to death, with two of the victims found partially unclothed from the waist down.

Despite the initial appearance, autopsies revealed that the women had not been sexually assaulted. Robbery also seemed an unlikely motive, as their watches and jewelry remained untouched. Investigators identified a frozen tree limb found near the scene as the suspected murder weapon, further deepening the mystery surrounding the Starved Rock State Park murders.

Chester Weger: The Starved Rock Lodge Dishwasher

At the center of the Starved Rock murders case is Chester Weger. In 1960, he was a 21-year-old dishwasher employed at the Starved Rock Lodge. Weger claimed he was on a break, alone in a room at the Lodge, during the estimated time of the murders. A husband, father, and veteran, Weger became infamously known as the “Starved Rock Murderer” and Illinois’ longest-incarcerated inmate.

Explore Photos Related to the Chester Weger Case

The Interrogation and Confession of Chester Weger

Chester Weger in a Police Lineup

Chester Weger in a Police Lineup

In the days following the grim discovery at Starved Rock State Park, Chester Weger was among numerous individuals questioned by Illinois State Police investigators. He underwent further questioning about a month later and passed multiple polygraph tests. However, approximately six months after the murders, in late September, LaSalle County Sheriff’s Deputy William Dummett took Weger to Chicago for another polygraph examination. According to Deputy Dummett, Weger failed this test. Dummett then reportedly attempted to coerce a confession from Weger, who maintained his innocence. During the return drive from Chicago, Deputy Dummett allegedly threatened Weger with the electric chair if he did not confess.

In October, the Illinois State Police initiated continuous surveillance of Weger, which lasted for over a month. On November 16, 1960, Weger was brought in by LaSalle County authorities for yet another round of questioning. Despite hours of interrogation, he continued to deny any involvement in the Starved Rock murders. Later that night, despite the absence of physical evidence linking him to the crime scene and no witnesses placing him at the park, warrants were issued for Weger’s arrest. He was placed in a lineup related to a robbery and rape that had occurred in Deer Park in 1959. The interrogation resumed, and Weger claimed he was again threatened with the electric chair if he refused to confess.

After prolonged interrogation, sleep deprivation, months of surveillance, and repeated threats, Chester Weger confessed to Deputy Dummett shortly before 2:00 a.m. on November 17, 1960. This confession came after what Weger described as relentless pressure and fear of execution.

However, Weger recanted his confession before his trial, asserting it was a product of police coercion and threats. Despite his testimony and the lack of physical evidence connecting him to the brutal crime scene, the jury found Chester Weger guilty, though they spared him the death penalty.

Key Timeline of Events:

- 11/16/60: Chester Weger arrested.

- 11/17/60: Chester Weger confesses to the Starved Rock murders.

- 11/19/60: Chester Weger recants his confession.

- 01/20/61: Criminal trial begins.

- 02/27/61: Chester Weger testifies in his own defense.

- 03/03/61: Jury finds Chester Weger guilty.

- 04/03/61: Chester Weger sentenced to life in prison.

The Legal Landscape of the 1960s

Chester Weger’s trial occurred before two pivotal Supreme Court decisions that significantly altered legal procedures regarding criminal prosecutions. In 1963, the Supreme Court ruling in Brady v. Maryland, 373 U.S. 83 (1963) established the prosecution’s obligation to disclose any exculpatory evidence – evidence favorable to the defendant that could potentially prove innocence – to the defense. Critically, at the time of Weger’s trial, prosecutors were not legally bound to share such evidence. This meant that if prosecutors possessed information implicating another suspect in the Starved Rock murders, they were under no legal obligation to provide it to Weger or his defense attorney.

In 1966, the Supreme Court’s decision in Miranda v. Arizona, 384 U.S. 436 (1966), mandated that law enforcement officers inform detained suspects of their constitutional rights – the right to an attorney and the right to remain silent – before interrogation. Had Miranda been established law in 1961, deputies would have been required to advise Weger of these rights before questioning him. Crucially, had Weger requested legal counsel, the interrogation would have had to cease, potentially preventing the confession altogether.

Factors Casting Doubt on Weger’s Guilt in the Starved Rock Murders

Numerous elements raise serious questions about the validity of Chester Weger’s confession and bolster his claims of innocence in the Starved Rock State Park murders. Notably, no physical evidence directly linked Weger to the gruesome crime scene, and no witnesses placed him at St. Louis Canyon. Conversely, physical evidence emerged that arguably supports his exoneration. A blond hair found on Frances Murphy’s glove was analyzed by Eastman Kodak and determined to be dissimilar to Weger’s hair. Black hairs were also discovered in Lillian Oetting’s palm, and Weger did not have black hair. Despite the collection and analysis of multiple hair and fiber samples, this crucial hair evidence was not presented at Weger’s trial. The presence of both blond and black hairs on the victims suggests the possibility of two perpetrators involved in the Starved Rock murders. Furthermore, the physical capability of the 5’8” Weger to overpower and subdue three women remains questionable.

Weger passed several polygraph examinations in the immediate aftermath of the murders. The rationale for administering another polygraph test six months later is unclear, and the claim that Weger failed this later exam is highly suspect.

The assertion that Weger’s confession was coerced is strengthened by Deputy Dummett’s alleged threat of the electric chair. Threats of death are a well-documented factor leading to false confessions. Moreover, Weger’s confession itself contains inconsistencies. He cited robbery as the motive, yet the victims’ jewelry was untouched. His claim that one of the women initiated the altercation by attacking him, as stated in the confession, also strains credibility.

Decades after Weger’s conviction, a juror admitted in a 2016 Tribune interview that she found Weger’s confession “implausible” even at the time of the trial. Weger’s current legal team, Andy Hale and Celeste Stack, argue that a case built on such flimsy evidence and questionable confession would not proceed to trial under contemporary legal standards.

Adding another layer of intrigue to the Starved Rock murders case is an alleged deathbed confession from an anonymous woman in 1982. Sergeant Mark Gibson recounted in a 2006 affidavit that he visited a hospital to allow the woman to “clear her conscience.” The woman reportedly confessed that “things got out of hand” at a state park and “they dragged the bodies.” Gibson stated that the confession was abruptly ended by the woman’s daughter, who claimed her mother was not mentally sound. While circumstantial, this incident raises the question of whether it could be connected to the Starved Rock murders.

Throughout his long incarceration, Chester Weger consistently maintained his innocence. In a 1963 letter to the Chicago Tribune, Weger declared, “Now there’s nothing in the world that I needed bad enough to kill for.” Supporters rallied around him, launching a “Friends of Chester Weger” Facebook page in 2013, which garnered nearly two thousand followers. In 2016, he reiterated to the Tribune his unwavering stance, stating he would rather die in prison than falsely admit guilt. Despite his persistent efforts to prove his innocence, Weger’s plea for clemency was denied in 2007.

Chester Weger’s Parole and the Ongoing Quest for Exoneration

Chester Weger After Release from Prison

Chester Weger After Release from Prison

On November 20, 2019, after 23 previous rejections, the Illinois Prisoner Review Board voted 9-4 to grant Chester Weger parole. Having served 61 years, he was the second-longest serving inmate in Illinois history at the time of his release. Weger’s attorneys, Andy Hale and Celeste Stack, expressed their elation at his release and pledged to continue the fight to fully exonerate him. Lead counsel Hale told ABC7 news: “[We are very pleased that Chester was released today into the arms of his devoted family, who have waited decades for this day.]” The Starved Rock State Park murders case remains a chilling reminder of the potential for wrongful convictions and the enduring pursuit of justice, even decades later.