Rocks are fundamental to our planet, forming the very ground beneath our feet and the majestic landscapes around us. In geology, a rock is defined as a naturally occurring, coherent aggregate of one or more minerals. These aggregates are the basic units composing the solid Earth and typically form recognizable and mappable volumes. Understanding what defines a rock is crucial to grasping geological processes and the Earth’s history.

Various sizes of rocks, from sand grains to a car-sized boulder, illustrating the broad range in rock dimensions.

Various sizes of rocks, from sand grains to a car-sized boulder, illustrating the broad range in rock dimensions.

Rocks come in an astonishing variety of forms, each telling a story about its formation and the Earth’s dynamic processes. They are not simply random collections of minerals; their characteristics and classifications are based on specific geological criteria. Let’s delve deeper into the definition of rock and explore its key aspects.

What Constitutes a Rock? Key Characteristics

To truly define a rock, we need to break down its essential characteristics. Three key elements define what geologists classify as a rock:

Mineral Composition: The Building Blocks

Rocks are essentially composed of minerals. Minerals are naturally occurring, inorganic solids with a defined chemical composition and crystal structure. A rock can be made up of a single mineral, like quartzite which is primarily composed of quartz, or, more commonly, it’s an aggregate of several different minerals. For example, granite is a common rock composed of minerals like quartz, feldspar, and mica. The specific types and proportions of minerals within a rock significantly influence its properties and classification.

Coherent Aggregate: Holding it All Together

The term “coherent” in the definition of rock implies that the mineral components are bound together. This cohesion gives rock its solid and durable nature. The minerals within a rock are held together by chemical bonds, interlocking crystal structures, or cementing materials. This coherence distinguishes a rock from loose sediments like sand or soil, where individual particles are not firmly bound.

Naturally Occurring: Formed by Earth’s Processes

Rocks are formed by natural geological processes. This distinguishes them from human-made materials like concrete or bricks. These natural processes include the cooling and solidification of molten magma, the accumulation and cementation of sediments, and the transformation of existing rocks through heat, pressure, or chemical reactions. The origin of a rock is a primary factor in its classification, leading to the three main types of rocks: igneous, sedimentary, and metamorphic.

The Three Major Types of Rocks

Rocks are broadly classified into three major classes based on their formation processes:

Igneous Rocks: Born from Fire

Igneous rocks, also known as magmatic rocks, are formed from the solidification of molten rock material called magma or lava. Magma is molten rock found beneath the Earth’s surface, while lava is magma that has erupted onto the surface.

- Formation: Igneous rocks crystallize from magma or lava as they cool. The cooling rate influences the crystal size; slow cooling beneath the surface leads to larger crystals (intrusive igneous rocks), while rapid cooling on the surface results in smaller crystals or even volcanic glass (extrusive igneous rocks).

- Examples: Granite and diorite are examples of intrusive igneous rocks. Basalt and obsidian are extrusive varieties.

Sedimentary Rocks: Layers of History

Sedimentary rocks are formed from the accumulation and lithification of sediments. These sediments can be fragments of pre-existing rocks, mineral precipitates from solutions, or organic matter.

- Formation: Sedimentary rocks are created through a series of processes: weathering and erosion of existing rocks, transportation of sediments by water, wind, or ice, deposition of sediments in layers, and lithification. Lithification involves compaction and cementation, where sediments are squeezed together, and minerals precipitate to bind the particles.

- Stratification: A key characteristic of sedimentary rocks is stratification, or layering. These layers can be distinguished by differences in color, grain size, mineral composition, and the type of cement.

- Examples: Sandstone, shale, and limestone are common sedimentary rocks. Fossils are frequently found within sedimentary layers, providing valuable insights into Earth’s past life.

Metamorphic Rocks: Transformation Under Pressure

Metamorphic rocks are formed when existing rocks – igneous, sedimentary, or even other metamorphic rocks – are transformed by heat, pressure, or chemically active fluids.

- Formation: Metamorphism occurs deep within the Earth’s crust where temperatures and pressures are high enough to alter the mineralogy, texture, and structure of the original rocks. This transformation occurs in the solid state, without complete melting.

- Recrystallization: Metamorphic processes often lead to recrystallization, where minerals change their size and arrangement. This can result in new and different minerals forming.

- Banding: Metamorphism can also create a layered or banded appearance in rocks, known as foliation, due to the alignment of minerals under pressure.

- Examples: Marble (from limestone), quartzite (from sandstone), and slate (from shale) are common metamorphic rocks.

The Rock Cycle: An Endless Transformation

The rock cycle is a fundamental concept in geology that describes the continuous transformations between the three main types of rocks. It’s a dynamic process driven by Earth’s internal heat and external forces like weathering and erosion.

- Melting: Igneous rocks form when any rock type melts into magma and subsequently solidifies.

- Weathering and Erosion: Sedimentary rocks originate from the weathering and erosion of any existing rock type, followed by deposition and lithification of the resulting sediments.

- Metamorphism: Metamorphic rocks are produced when any pre-existing rock is subjected to metamorphic conditions.

The rock cycle highlights that rocks are not static entities but are constantly being recycled and transformed over geological time. This cycle explains the interconnectedness of different rock types and their role in shaping the Earth’s crust.

Rock Texture: Looking Closer at the Fabric

Examples of different rock textures, including layered sandstone, coquina, breccia, porphyry, obsidian, serpentine, talc schist, and gneiss banding, showcasing the variety in rock surfaces.

Examples of different rock textures, including layered sandstone, coquina, breccia, porphyry, obsidian, serpentine, talc schist, and gneiss banding, showcasing the variety in rock surfaces.

Rock texture refers to the size, shape, and arrangement of mineral grains or crystals within a rock. Texture provides valuable clues about a rock’s origin and geological history. Key aspects of texture include:

- Grain/Crystal Size: Descriptive terms like coarse-grained, medium-grained, and fine-grained are used to classify rocks based on the size of their mineral components. For sedimentary rocks, grain size is crucial, while for igneous and metamorphic rocks, crystal size is considered.

- Homogeneity: Homogeneity describes the uniformity of mineral composition throughout the rock. Some rocks are homogenous, with consistent mineral distribution, while others are heterogeneous.

- Isotropy: Isotropy refers to the uniformity of rock properties in all directions. This is related to the arrangement and orientation of mineral grains or crystals.

Analyzing rock texture helps geologists understand the conditions under which a rock formed, such as the cooling rate of magma, the depositional environment of sediments, or the metamorphic history of a rock.

Classification by Grain or Crystal Size

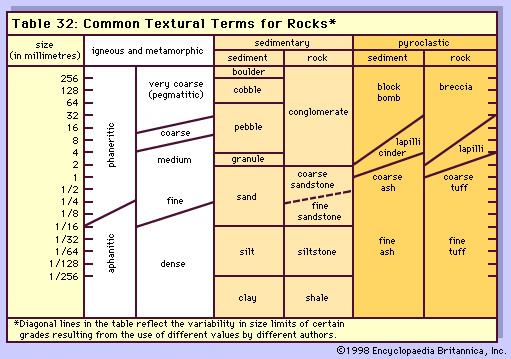

Table of rock textural terms based on grain or crystal size, derived from the Udden-Wentworth scale, used for classifying rocks by particle size.

Table of rock textural terms based on grain or crystal size, derived from the Udden-Wentworth scale, used for classifying rocks by particle size.

Classifying rocks by grain or crystal size is a common method, particularly useful for sedimentary and igneous rocks. The Udden-Wentworth scale provides a standard for sediment particle size classification, which is also applied to rocks.

- Sedimentary Rock Grain Sizes: Sediments are broadly categorized as coarse (gravel, pebbles), medium (sand), and fine (silt, clay) based on particle size. These categories are reflected in sedimentary rock names like conglomerates (coarse), sandstones (medium), and shales (fine).

- Igneous and Metamorphic Crystal Sizes: For igneous and metamorphic rocks, terms like coarse-grained (phaneritic), medium-grained, and fine-grained (aphanitic) describe crystal size. Pegmatitic describes exceptionally coarse-grained rocks with crystals larger than 3 centimeters.

This classification helps in identifying and comparing different rock types based on the visual and tactile properties related to their grain or crystal size.

Rock Porosity: The Empty Spaces Within

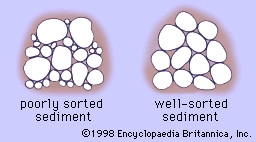

Illustration of rock sorting, demonstrating well-sorted sediment with uniform grain sizes and poorly sorted sediment with a wide range of grain sizes, affecting porosity.

Illustration of rock sorting, demonstrating well-sorted sediment with uniform grain sizes and poorly sorted sediment with a wide range of grain sizes, affecting porosity.

Porosity refers to the volume of void space within a rock, expressed as a percentage of the total rock volume. This void space includes pores between grains or crystals and any cracks or fractures. Porosity is a crucial property that affects a rock’s ability to hold fluids like water, oil, or gas.

- Factors Affecting Porosity: Porosity in sedimentary rocks is influenced by factors like sediment compaction, grain shape and packing, the amount of cementation, and the degree of sorting. Well-sorted sediments, with uniform grain sizes, tend to have higher porosity than poorly sorted sediments.

- Total vs. Apparent Porosity: Total porosity encompasses all void spaces, while apparent (or effective) porosity only considers interconnected pore spaces accessible to fluids. Apparent porosity is more relevant for understanding fluid flow and storage in rocks.

Understanding rock porosity is essential in various applications, including groundwater hydrology, petroleum geology, and civil engineering.

Conclusion: Rocks as Records of Earth’s Processes

Defining a rock goes beyond simply calling it a hard, solid object. It involves understanding its mineral composition, coherent nature, and natural origin. Rocks are categorized into igneous, sedimentary, and metamorphic types, each formed through distinct geological processes. The rock cycle illustrates their continuous transformation, while texture, classification by size, and porosity further define their characteristics.

Rocks are not just inert materials; they are dynamic archives of Earth’s history, processes, and resources. By studying rocks, we gain insights into our planet’s past, present, and future. Explore more about the fascinating world of rocks and their diverse landscapes at rockscapes.net.