Planet Earth, our home, is a fascinating sphere composed of distinct layers, each with unique chemical and physical properties. While the Earth’s core is dominated by iron and nickel, the mantle and crust, which make up the lithosphere, are primarily built from silicate rocks. It’s within this lithosphere that the constant cycle of rock formation and reformation takes place.

The creation of rocks is not a single process but rather a diverse set of geological events, varying significantly depending on the type of rock in question. Geologists classify rocks into three major categories: igneous, sedimentary, and metamorphic. Each of these rock types originates from fundamentally different processes, meaning that to answer the question, “How Are Rocks Formed?”, we must explore three distinct pathways.

The Fiery Birth of Igneous Rocks

Igneous rocks, aptly named “fire-formed” rocks, are born from the cooling and solidification of molten rock. This molten rock exists in two primary forms: magma and lava. Magma is molten rock found beneath the Earth’s surface, stewing in the intense heat and pressure of the Earth’s interior. When this magma erupts onto the surface, often dramatically through volcanoes, it is then called lava. As lava flows across the landscape or magma slowly cools beneath the surface, it transitions from a liquid to a solid state, crystallizing into igneous rock.

Common examples of igneous rocks include granite, a coarse-grained rock often used in countertops, and obsidian, a glassy, volcanic rock sometimes used to make sharp tools. Pumice, another type of igneous rock, is created during explosive volcanic eruptions. When lava, rich in dissolved gases, is violently ejected, the rapid cooling and depressurization trap gas bubbles within the solidifying rock, resulting in a lightweight, porous stone.

Igneous rock formation process from magma cooling and solidification

Igneous rock formation process from magma cooling and solidification

Sedimentary Rocks: Layers of Time and Pressure

Sedimentary rocks tell a story of time and accumulation. Their formation begins with weathering and erosion, processes that break down existing rocks into smaller particles – sediments. These sediments, ranging from tiny grains of sand to larger pebbles, are transported by wind, water, and ice and eventually settle out, often in bodies of water like oceans, lakes, and rivers.

Over vast stretches of time, layer upon layer of sediment accumulates. The weight of these overlying layers compresses the lower layers, a process called compaction. Minerals dissolved in water percolating through the sediments then precipitate out, acting like natural cement to bind the sediment particles together. This process, known as cementation, transforms loose sediments into solid sedimentary rock.

Sandstone, a familiar sedimentary rock, originates from sand deposited on beaches or riverbeds. Limestone, another common type, often forms from the accumulation of shells and skeletal fragments of marine organisms. Shale, conglomerate, and gypsum are further examples of the diverse family of sedimentary rocks, each reflecting different types of sediment and depositional environments.

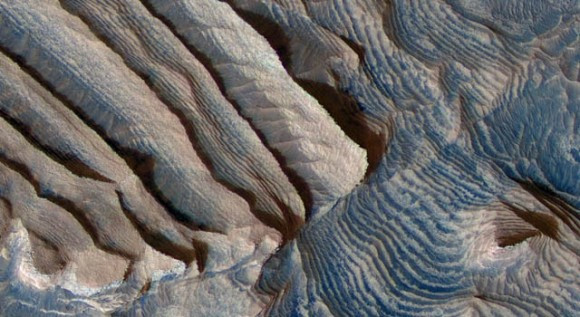

Sedimentary rock layers showing rhythmic bedding patterns

Sedimentary rock layers showing rhythmic bedding patterns

Metamorphic Rocks: Transformation Under Pressure and Heat

Metamorphic rocks are the result of dramatic transformations. The term “metamorphic” itself hints at change, derived from Greek words meaning “change of form.” These rocks begin as either igneous, sedimentary, or even pre-existing metamorphic rocks, but are then subjected to intense heat, pressure, or chemically active fluids deep within the Earth.

These extreme conditions cause significant changes to the original rock’s mineral composition, texture, or structure. For example, limestone, a sedimentary rock, can be transformed into marble under intense heat and pressure. The calcite crystals within the limestone recrystallize and grow, interlocking tightly to form the harder, denser marble prized for its beauty and durability. Similarly, shale can metamorphose into slate, and granite can become gneiss. Metamorphism is a powerful process that recycles and remakes rocks, demonstrating the dynamic nature of our planet’s crust.

Rocks are not static objects; they are constantly being formed, broken down, and reformed in a continuous cycle. Understanding how each type of rock is formed provides us with valuable insights into Earth’s geological history and the dynamic processes that shape our planet. From the fiery origins of igneous rocks to the layered stories of sedimentary rocks and the transformative power behind metamorphic rocks, each rock type offers a unique window into the Earth’s ever-changing geology.