Igneous rocks, born from fire, are a fundamental component of our planet’s geology. They tell a story of Earth’s intense internal heat and the dramatic processes that shape its surface. Formed from the cooling and crystallization of magma, molten rock found beneath the Earth’s surface, or lava, its surface counterpart, these rocks exhibit a stunning variety of compositions and textures. The journey from molten state to solid rock is what defines the fascinating world of igneous rocks.

The key to understanding the diversity of igneous rocks lies in two primary factors: the composition of the original magma and the conditions under which it cools. Magma originates deep within the Earth, in the lower crust or upper mantle, where temperatures are high enough to melt rock. The chemical makeup of this magma can vary significantly, leading to a wide array of igneous rock types. Furthermore, the rate at which magma cools plays a crucial role in determining the final appearance and characteristics of the rock. A striking example of this is how identical magma can solidify into either rhyolite or granite, simply based on whether the cooling process is rapid or slow.

Igneous rocks are broadly categorized into two main types based on their formation location: extrusive and intrusive.

Extrusive Igneous Rocks: Born on the Surface

Extrusive igneous rocks, also known as volcanic rocks, are created when lava erupts onto the Earth’s surface from volcanoes. This surface exposure leads to rapid cooling. Imagine molten lava flowing down a volcano – the sudden contact with the cooler atmosphere or ocean water causes it to solidify quickly. This rapid cooling process is the reason behind the fine-grained texture characteristic of extrusive rocks. Crystals within these rocks have limited time to grow, resulting in small, often microscopic crystals.

Rocks with such small crystals are termed aphanitic, derived from Greek words meaning “invisible.” The mineral crystals are so minute that they are usually indistinguishable without the aid of a microscope. Obsidian provides a dramatic illustration of rapid cooling. When lava cools almost instantaneously, it solidifies into a glassy rock with virtually no crystals, showcasing nature’s ability to create volcanic glass. Beyond obsidian, the world of extrusive rocks includes diverse forms like Pele’s hair, delicate strands of volcanic glass stretched thin by escaping gases, and pahoehoe lava, known for its smooth, undulating surfaces that solidify into shiny, rounded formations.

Intrusive Igneous Rocks: Forged Underground

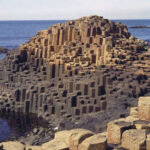

In contrast to their surface-born counterparts, intrusive igneous rocks, also called plutonic rocks, solidify deep within the Earth’s crust. Here, shielded from the rapid temperature changes at the surface, magma cools slowly over extended periods. This slow cooling allows for the development of large, well-formed crystals that are typically visible to the naked eye. This coarse-grained texture is known as phaneritic.

Granite stands as a quintessential example of a phaneritic rock and is perhaps the most recognized intrusive igneous rock. Its speckled appearance, due to the presence of various visible minerals, is a direct result of slow crystallization beneath the Earth’s surface. Pegmatite represents an extreme end of the phaneritic spectrum. Frequently found in regions like Maine, USA, pegmatites are characterized by exceptionally large crystals, sometimes exceeding the size of a human hand. These rocks display a remarkable variety of crystal shapes and sizes, showcasing the dramatic effects of prolonged, undisturbed cooling deep within the Earth.

In conclusion, igneous rocks present a fascinating study in contrasts, shaped by their origin and cooling history. From the fine-grained extrusive rocks formed in fiery surface eruptions to the coarse-grained intrusive rocks slowly crystallized in the Earth’s depths, each type provides valuable insights into the dynamic geological processes that have sculpted our planet over millennia. Exploring Igneous Rock Examples is a journey into understanding Earth’s powerful internal engine and its dramatic surface expressions.