Ice. We encounter it in our drinks, on winter roads, and in breathtaking glacial landscapes. It’s a familiar substance, often associated with cold and refreshment. But have you ever stopped to consider if ice is more than just frozen water? Surprisingly, in the world of geology, ice holds a fascinating dual identity. While we might intuitively think of rocks as hard, solid masses formed deep within the Earth, geologists broaden this definition to include materials formed by natural processes. This leads us to an intriguing question: Is Ice A Rock, and if so, is it also a mineral?

A stunning glacier landscape under a cloudy sky, showcasing the vastness and beauty of glacial ice.

A stunning glacier landscape under a cloudy sky, showcasing the vastness and beauty of glacial ice.

The answer might challenge your initial perceptions. Yes, ice is indeed recognized as a mineral, and in certain contexts, even classified as a rock by the United States Geological Survey (USGS). This might seem counterintuitive at first. After all, we learn about minerals and rocks as solid components of the Earth’s crust, not something as commonplace as ice. Yet, when we delve into the scientific definitions and properties of ice, its geological classification becomes clear.

What Makes Ice a Mineral?

To understand why ice qualifies as a mineral, we need to look at the geological definition. Minerals are defined by five key characteristics:

- Naturally occurring: Minerals must form through natural geological processes, not be created synthetically. Ice, in its natural forms like glaciers, snowflakes, and frozen lakes, clearly meets this criterion.

- Inorganic: Minerals are not composed of organic matter, meaning they are not formed by living organisms or their remains. Ice, composed of water molecules (H₂O), is an inorganic substance.

- Solid: At standard temperature and pressure on Earth’s surface, minerals are solid. Ice, in its typical state, is solid.

- Definite chemical composition: Minerals have a specific chemical formula. Ice is dihydrogen oxide, or H₂O, a precise and consistent chemical makeup.

- Ordered crystalline structure: Minerals possess a highly ordered arrangement of atoms in a repeating pattern, forming crystals. Ice crystallizes in a hexagonal system, giving snowflakes their iconic six-sided symmetry and forming various crystalline structures.

Close up of intricate ice crystals forming dendritic patterns on a windowpane, highlighting the crystalline nature of ice.

Close up of intricate ice crystals forming dendritic patterns on a windowpane, highlighting the crystalline nature of ice.

This crystalline structure is crucial. While liquid water, the source of ice, is not a mineral due to its lack of a fixed structure and solid state at room temperature, the transformation to ice changes everything. Water molecules in ice arrange themselves in a specific, repeating pattern held together by hydrogen bonds. This ordered structure is what elevates ice from mere “frozen water” to a legitimate mineral. In fact, ice has been assigned the Dana mineral classification number 04.01.02.01, and it receives extensive mineralogical description in authoritative resources like Dana’s System of Mineralogy.

It’s interesting to note the concept of mineraloids. Substances like opal and obsidian are considered mineraloids because they lack a crystalline structure, even though they share other mineral characteristics. Water, in its liquid form, is also considered a mineraloid. However, ice transcends this classification by achieving that crucial crystalline order.

The Crystalline Nature and Colors of Ice

The crystalline structure of ice dictates many of its properties, including its color and the diverse forms it takes. Pure ice is transparent to translucent and typically appears colorless or white, especially in smaller quantities like ice cubes. However, larger masses of ice, such as glaciers and icebergs, often exhibit a captivating bluish tint.

This blue color arises from the way ice interacts with light. Hydrogen bonds within the ice crystal lattice absorb red wavelengths of light more effectively than blue wavelengths. As light travels through a significant thickness of ice, more red light is absorbed, leaving the blue wavelengths to be reflected and scattered back to our eyes, resulting in the characteristic blue hue of glaciers.

A large block of clear ice, showcasing its transparency and potential for use in ice sculptures or drinks.

A large block of clear ice, showcasing its transparency and potential for use in ice sculptures or drinks.

Ice exhibits a remarkable variety of forms, known as crystal habits. Massive ice, lacking distinct crystal faces, forms when water freezes rapidly or when ice crystals are compressed. Examples of massive ice are seen in frozen lakes, glaciers, icicles (stalactites of ice), and hailstones (concentric concretions of ice).

Crystalline ice, on the other hand, develops when water freezes slowly or when water vapor deposits directly as a solid. This slower formation allows for the development of intricate crystal shapes. Snowflakes are perhaps the most iconic example of crystalline ice. They form when water vapor in the atmosphere freezes onto tiny particles like pollen or dust, creating seed crystals. Water vapor then crystallizes onto these seeds in an orderly fashion, dictated by ice’s hexagonal structure.

The final shape of a snowflake is a complex interplay of atmospheric conditions, including temperature, humidity, time spent aloft, and wind. Warmer air tends to produce simpler snowflake shapes, while colder air leads to the formation of more elaborate and complex dendritic structures. The incredible variability in these atmospheric factors explains why no two snowflakes are ever exactly alike. From the delicate dendritic growths on windowpanes to the flat, lathlike crystals of pond skim ice and the stellar dendrites of snowflakes, the crystalline world of ice is incredibly diverse.

Ice as a Rock: Igneous, Sedimentary, and Metamorphic

Beyond being a mineral, the USGS also classifies ice as a rock. This might seem even more surprising, but when we consider the geological definition of a rock, it becomes understandable. Rocks are generally defined as naturally occurring solid aggregates of minerals. While ice is composed of a single mineral (ice itself), geological classifications sometimes broaden the definition of rock to encompass large masses of a single mineral, especially when formed through geological processes similar to those that create other rock types.

In this context, ice can be seen to parallel the three main categories of rocks: igneous, sedimentary, and metamorphic.

-

Igneous Ice: Just as igneous rocks like basalt and rhyolite solidify from molten magma, the ice in a frozen pond can be considered a solidified melt. The rate of cooling, similar to igneous rock formation, affects the texture of the ice. Slowly cooled water results in coarsely textured massive ice, while rapid freezing produces fine-textured ice or even “ice glass,” analogous to obsidian, a natural volcanic glass formed from rapidly cooled magma.

-

Sedimentary Ice: Snow, before it transforms into glacial ice, can be compared to a sedimentary deposit, akin to sand dunes. As snow accumulates, thaws, and refreezes, it compacts and consolidates, much like the processes that form sedimentary rocks. Furthermore, ice can act as a cementing agent, binding sand or soil particles together into hard masses, similar to how silica cements sedimentary rocks. This is evident in permafrost regions, where permanently frozen ground is created by ice cementing soil.

-

Metamorphic Ice: When ice is deeply buried within glaciers or ice caps, the immense pressure can cause recrystallization, transforming it into a metamorphic form. Glacial ice, in its texture, can resemble fine-grained metamorphic rocks like marble and quartzite. The weight and movement of glaciers can also deform and contort ice into complex folds and structures, mirroring the formations seen in metamorphic gneiss and schist.

A vast glacier landscape with crevasses and snow, illustrating the scale and metamorphic nature of glacial ice.

A vast glacier landscape with crevasses and snow, illustrating the scale and metamorphic nature of glacial ice.

Like other rocks, ice is also utilized as a building material. The Inuit people of the Arctic traditionally construct igloos from blocks of ice. Ice palaces are built for winter festivals in various northern regions. Historically, large quantities of ice were harvested from frozen lakes and used for refrigeration. Even today, ice serves as a medium for sculpting in seasonal ice-carving events.

Glaciology and Ice Cores: Studying Ice as a Rock Record

The scientific discipline dedicated to the study of glaciers and other ice-related phenomena is called glaciology, derived from the Latin word “glacies” meaning “frost” or “ice.” Glaciologists study glaciers as dynamic geological features. Glaciers are perennial accumulations of ice, snow, rock, and sediments that originate on land and move downslope due to gravity and their own weight. They range in size from massive continental ice sheets to smaller alpine glaciers. Glacier movement speeds vary significantly, from fast-moving glaciers that can travel up to 100 feet per day to slow-moving ones progressing only inches daily. The average glacier movement is estimated at around 12 inches per day, a rate that is, unfortunately, increasing with global warming.

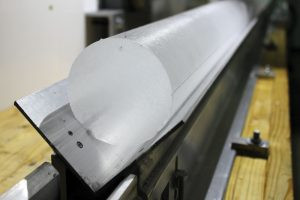

An ice core sample being examined in a lab, showcasing the layers of ice that provide historical climate data.

An ice core sample being examined in a lab, showcasing the layers of ice that provide historical climate data.

Glaciologists and climate scientists utilize ice cores as invaluable archives of Earth’s past climate. Since the 1960s, scientists have been drilling ice cores from glaciers and ice sheets. These cores reveal sequential layers of ice, with each layer representing a year of snowfall, much like tree rings document annual growth. These layers can be precisely dated, providing a chronological record of past atmospheric conditions. Each layer encapsulates a chemical and physical snapshot of the atmosphere at the time the ice formed.

“Reading” Ice: Unlocking Earth’s Past

By analyzing ice cores, scientists can “read” the ice to reconstruct past environmental conditions. Measuring oxygen isotope levels in air bubbles trapped within the ice allows for the compilation of a continuous record of global temperatures stretching back hundreds of thousands of years. This record reveals that Earth’s climate has been largely unstable for the past 250,000 years, with the relatively stable climate of the last 10,000 years being an exception.

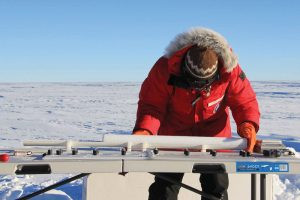

A scientist in Antarctica preparing a freshly extracted ice core for transport, highlighting the field work involved in ice core research.

A scientist in Antarctica preparing a freshly extracted ice core for transport, highlighting the field work involved in ice core research.

Ice cores also contain evidence of past volcanic eruptions, indicated by layers rich in volcanic ash and sulfur. Layers with high carbon and biological matter content point to large-scale forest fires. Intriguingly, sequences of sulfur- and lead-rich ice layers dating back to the second century CE provide an atmospheric record of extensive silver and lead smelting activities during the Roman Empire.

The ice-core record has even revealed connections between past climate events and human history. For example, evidence from ice cores suggests that the cataclysmic eruption of Alaska’s Okmok volcano in 43 BCE triggered decades of global cooling, leading to agricultural failures, famine, political instability, and social unrest, potentially contributing to the collapse of the Roman Republic in 31 BCE.

In conclusion, ice is far more than just frozen water. It is a mineral, meeting all the criteria defined by geologists. Furthermore, in its various geological forms and processes, ice can also be classified as a rock, comparable to igneous, sedimentary, and metamorphic rock types. Ice is a substance of remarkable beauty, a dynamic geological force, and an invaluable archive of Earth’s past, offering us critical insights into our planet’s climate history and environmental changes.