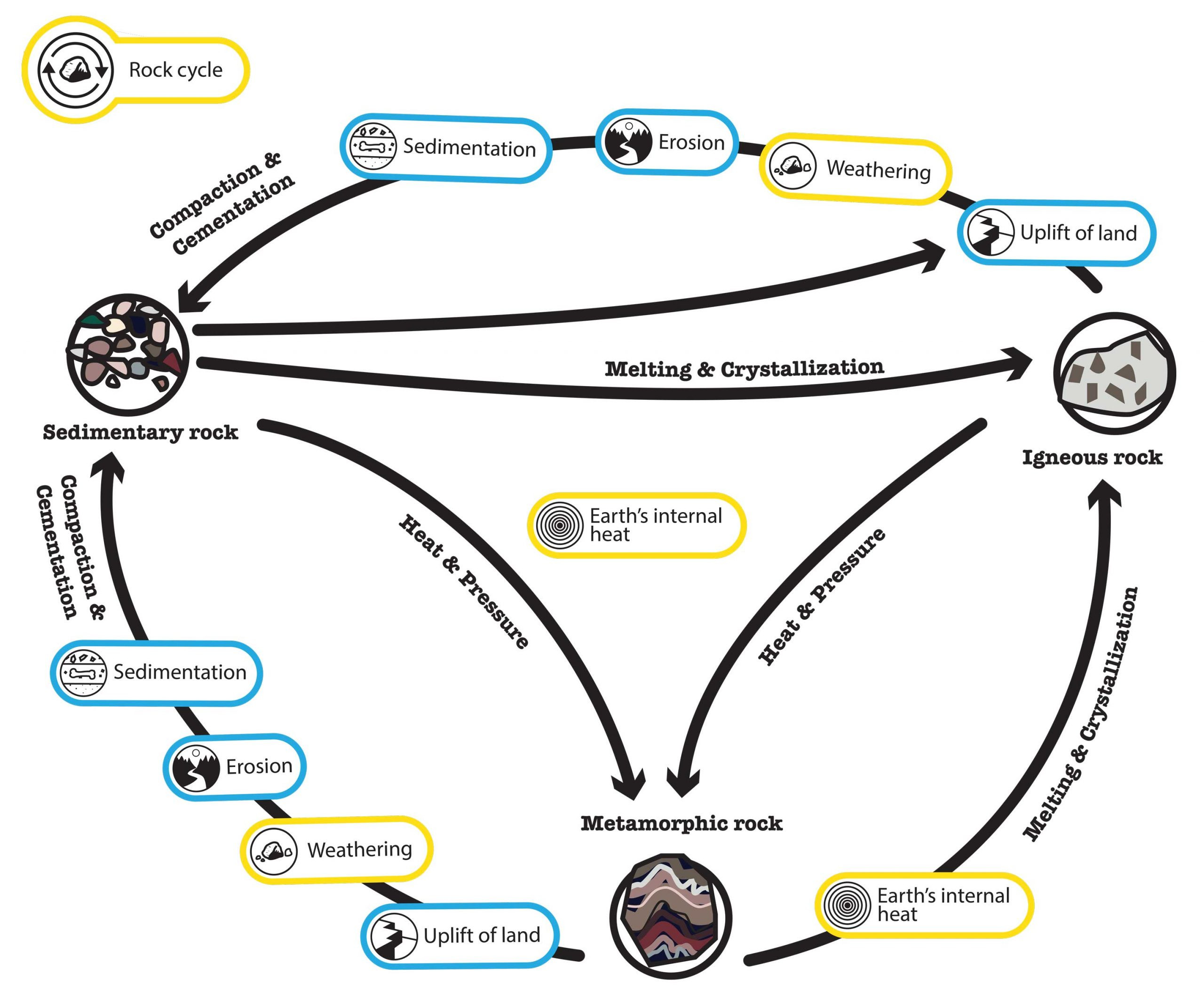

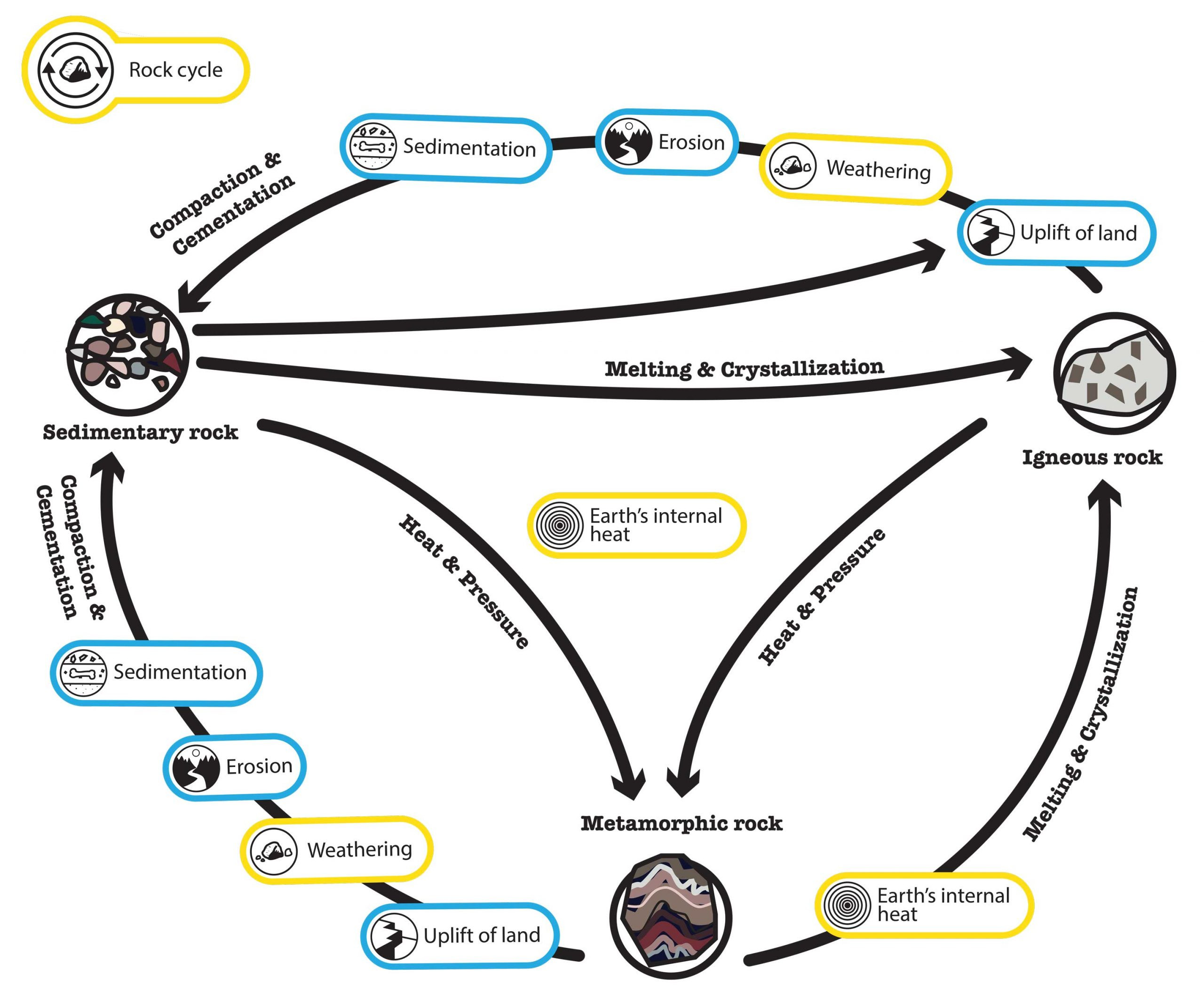

Rocks are fundamental building blocks of our planet, each telling a unique story of Earth’s dynamic processes. They aren’t static; instead, they are continuously transformed through a series of geological processes known as the Rock Cycle. This cycle illustrates how rocks change between three main types – igneous, sedimentary, and metamorphic – in response to Earth’s internal and external forces. Understanding the rock cycle is key to grasping Earth’s history, the formation of landscapes, and even the impact of human activities on our planet.

The Three Families of Rocks: Igneous, Sedimentary, and Metamorphic

Imagine Earth as a giant kitchen where rocks are the ingredients, and geological processes are the chefs, constantly cooking and transforming these ingredients. The rock cycle results in three main types of rocks, each formed under different conditions:

- Igneous Rocks: Born from Fire. Derived from the Latin word “ignis” meaning fire, igneous rocks are born from the cooling and solidification of molten rock. This molten rock, known as magma when beneath the surface and lava when erupted onto the surface, originates from deep within the Earth’s mantle or crust. When magma cools slowly beneath the Earth’s surface, it forms intrusive igneous rocks like granite, characterized by larger crystals. Conversely, when lava cools rapidly on the surface, often from volcanoes, it forms extrusive igneous rocks like basalt, which have smaller or even glassy textures due to rapid cooling.

Basalt columns at Giant's Causeway, Northern Ireland, showcasing extrusive igneous rock formation

Basalt columns at Giant's Causeway, Northern Ireland, showcasing extrusive igneous rock formation

- Sedimentary Rocks: Layers of Time. Sedimentary rocks are formed from the accumulation and cementation of sediments – fragments of pre-existing rocks, minerals, and organic material. The journey begins with weathering and erosion, processes that break down rocks at the Earth’s surface into smaller pieces. These sediments are then transported by wind, water, or ice and eventually deposited in layers. Over time, compaction and cementation of these layers solidify them into sedimentary rocks. Common examples include sandstone, formed from sand grains; shale, from clay particles; and limestone, often from the remains of marine organisms.

Sedimentary layers visible in canyon walls, illustrating the formation process over time

Sedimentary layers visible in canyon walls, illustrating the formation process over time

- Metamorphic Rocks: Transformation Under Pressure. Metamorphic rocks are the result of transforming existing rocks – igneous, sedimentary, or even other metamorphic rocks – through intense heat and pressure. This transformation, known as metamorphism, occurs deep within the Earth’s crust, often during mountain building events or near tectonic plate boundaries. The heat and pressure cause changes in the rock’s mineral composition and texture, without melting it entirely. For instance, shale, a sedimentary rock, can be metamorphosed into slate, and limestone can become marble.

Basalt columns at Giant's Causeway, Northern Ireland, showcasing extrusive igneous rock formation

Basalt columns at Giant's Causeway, Northern Ireland, showcasing extrusive igneous rock formation

The Continuous Cycle: Processes Driving Rock Transformation

The rock cycle is a continuous loop driven by several key Earth processes. Here’s how the cycle unfolds:

- Melting: Deep within the Earth, intense heat causes rocks to melt, forming magma. This magma is the starting point for igneous rocks.

- Cooling and Crystallization: Magma, either beneath the surface or erupted as lava, cools and solidifies. As it cools, minerals crystallize, forming igneous rocks.

- Weathering and Erosion: At the Earth’s surface, rocks are exposed to weathering – the breakdown of rocks by physical, chemical, and biological processes. Erosion then transports these weathered fragments, or sediments, away from their source.

- Sedimentation: Sediments are deposited in basins, such as oceans, lakes, and river valleys, accumulating in layers.

- Compaction and Cementation: Over time, the weight of overlying sediments compresses the lower layers (compaction). Minerals precipitate from groundwater, binding the sediments together (cementation), forming sedimentary rocks.

- Metamorphism: When rocks are subjected to intense heat and pressure, they undergo metamorphism, transforming into metamorphic rocks.

- Uplift and Exposure: Tectonic forces can uplift deeply buried rocks, bringing them to the surface where they are again subjected to weathering and erosion, restarting the cycle.

This cycle isn’t a simple, linear path. Rocks can transition through different stages in various orders. For example, a sedimentary rock can be metamorphosed, then uplifted and eroded to form new sediments, which might eventually become another sedimentary rock, or even melt to form igneous rocks.

Human Activities and the Rock Cycle

The rock cycle, while a natural Earth process, is significantly influenced by human activities. Our actions can accelerate or alter certain stages of the cycle, often with environmental consequences:

- Resource Extraction: Mining and quarrying for rocks and minerals for construction, industry, and energy resources drastically alter landscapes, expose rocks to faster weathering, and increase erosion rates.

- Fossil Fuel Extraction and Burning: Extraction of fossil fuels and their combustion contribute to climate change, which in turn impacts weathering rates through changes in temperature and precipitation patterns.

- Urbanization and Land Use Change: Paving land for urban development increases water runoff, leading to greater erosion in surrounding areas and altering sediment deposition patterns. Deforestation and agriculture can destabilize soils, accelerating erosion significantly.

- Damming Rivers: Dams alter sediment transport and deposition, impacting downstream ecosystems and coastal areas by trapping sediments that would naturally replenish beaches and deltas.

The Rock Cycle within the Earth System

The rock cycle is intricately linked to other Earth systems, such as the water cycle, the carbon cycle, and plate tectonics. For example, weathering processes are heavily influenced by water and temperature (water cycle). The burial of sediments plays a crucial role in the long-term carbon cycle. Plate tectonics drives mountain building, which leads to metamorphism and uplift, exposing rocks to weathering.

Understanding the rock cycle in the context of these broader Earth systems is essential for comprehending the complex interactions that shape our planet. By studying the rock cycle, we gain insights into Earth’s past, present, and future, and the profound impact of both natural processes and human activities on our ever-changing crust.