Thanks to the surge in popularity of crime dramas, podcasts, and documentaries, the public is now significantly more informed about legal and investigative procedures. One area that has gained considerable media attention is the troubling issue of false or coerced confessions within the justice system. Not long ago, a confession was often considered the definitive evidence in a criminal case. A defendant who had confessed, even if they later retracted it before trial, faced a slim chance of acquittal, regardless of any exonerating evidence. However, we now understand that individuals sometimes falsely confess to crimes they did not commit, often due to factors like being threatened with severe penalties by law enforcement. The decades-old wrongful conviction case of the Starved Rock Park Murders exemplifies this very situation.

In March 1960, the tranquil setting of Starved Rock State Park in Utica, Illinois, became the scene of a brutal triple homicide. Three women were savagely murdered, an event that shocked the small town and quickly escalated into a national news story. Eight months after the discovery of the slain women, Chester Weger, a 21-year-old dishwasher employed at the Starved Rock Lodge, confessed to the horrific crimes. However, before his trial commenced, Weger recanted his confession, proclaiming his innocence. Now, over six decades later, at 81 years old, Chester Weger has been granted parole but continues his fight to clear his name, seeking to prove he was wrongly convicted in the infamous Starved Rock Park murders case.

The Grisly Discovery at Starved Rock State Park

Starved Rock State Park entrance sign, Illinois, location of the infamous Starved Rock Park murders in 1960, a case involving Chester Weger and alleged wrongful conviction.

Starved Rock State Park entrance sign, Illinois, location of the infamous Starved Rock Park murders in 1960, a case involving Chester Weger and alleged wrongful conviction.

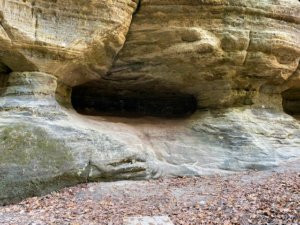

On Monday, March 14, 1960, Mildred Lindquist, 50, Frances Murphy, 47, and Lillian Oetting, 50, three women from Chicago, embarked on what was intended to be a relaxing four-day getaway to the popular natural beauty spot, Starved Rock Park near Utica, Illinois. Upon arriving and checking into the Starved Rock Lodge that morning, the women enjoyed lunch before setting off for a hike in the picturesque St. Louis Canyon area within the park. Tragically, these women would never be seen alive again.

When attempts to contact the women on Monday evening and Tuesday morning proved unsuccessful, their families grew increasingly worried. By Wednesday morning, with still no word from the women, a search party was organized. Just hours later, the search team made a gruesome discovery: the bloodied and battered bodies of the three women were found inside a small cave within St. Louis Canyon. The women had been brutally bludgeoned about the head, and two of the victims were found naked from the waist down.

Despite the victims’ partially unclothed state, the subsequent autopsy determined that sexual assault was not a factor in the murders. Investigators also ruled out robbery as a motive, as the women’s watches and jewelry remained untouched. A frozen tree limb discovered nearby was identified as the likely murder weapon used in the Starved Rock Park murders.

Chester Weger: From Lodge Dishwasher to Convicted Killer?

At the time of the Starved Rock Park murders, Chester Weger was a young 21-year-old working as a dishwasher at the Starved Rock Lodge. He testified that he was on a break alone in a room at the Lodge during the estimated time of the murders. Weger, a married father and veteran, would later become known as Illinois State’s longest-serving inmate and infamously branded as the “Starved Rock Murderer.”

View Photos from the Chester Weger Case

The Coerced Confession: The Ticking Clock

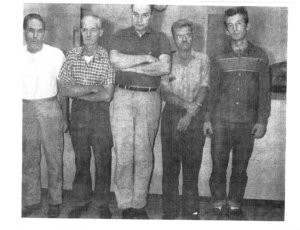

Chester Weger in a police lineup, raising questions about the fairness of the investigation in the Starved Rock Park murders case.

Chester Weger in a police lineup, raising questions about the fairness of the investigation in the Starved Rock Park murders case.

In the days immediately following the discovery of the women’s bodies in Starved Rock Park, Chester Weger was among those questioned by Illinois State Police investigators. He was interrogated again approximately a month later, and on both occasions, Chester passed polygraph examinations. However, about six months after the murders, in late September, LaSalle County Sheriff’s Deputy William Dummett picked up Chester and transported him to Chicago for yet another polygraph test. Throughout that day, Chester was subjected to intense interrogation. Deputy Dummett asserted that Chester had failed the polygraph and attempted to coerce him into confessing, but Chester maintained his innocence regarding the Starved Rock Park murders.

During the drive back from Chicago, Deputy Dummett reportedly made repeated threats to Chester, stating that if he did not sign a confession, he would face the electric chair. Shortly after this encounter, in October, the Illinois State Police initiated continuous surveillance of Chester, with teams of troopers following him constantly for over a month. On November 16, 1960, LaSalle County authorities once again brought Chester in for questioning. Despite hours of interrogation, Chester continued to assert his innocence in the Starved Rock Park murders.

Later that night, despite the absence of any physical evidence linking Chester to the crime scene, no witnesses placing him at Starved Rock Park during the murders, and Chester’s consistent denials, arrest warrants were issued. Chester was placed in a lineup related to a robbery and a rape that had occurred in Deer Park in 1959, incidents unrelated to the Starved Rock Park murders. He was then subjected to further interrogation, where he was allegedly told that failure to confess would result in a death sentence via the electric chair.

After being kept awake and interrogated for over 24 hours in September, followed by nearly two months of constant police surveillance, the threats of the electric chair from Deputy Dummett, and the pressure of the murder warrants, Chester Weger, shortly before 2:00 a.m. on November 17, 1960, finally provided Deputy Dummett with a confession to the Starved Rock Park murders.

Following his arrest, but before his criminal trial, Chester recanted his confession, stating it was a product of police coercion and threats. Despite testifying in his own defense and the lack of physical evidence connecting him to the bloody crime scene, the jury found Chester guilty, although they spared him the death penalty.

Timeline of Key Events: Starved Rock Park Murders Case

- 11/16/60: Chester Weger is arrested for the Starved Rock Park murders.

- 11/17/60: Chester Weger confesses to the Starved Rock Park murders.

- 11/19/60: Chester Weger recants his confession in the Starved Rock Park murders case.

- 01/20/61: Criminal trial for the Starved Rock Park murders commences.

- 02/27/61: Chester Weger testifies in his own defense during the Starved Rock Park murders trial.

- 03/03/61: The jury finds Chester Weger guilty of the Starved Rock Park murders.

- 04/03/61: Chester Weger is sentenced to life in prison for the Starved Rock Park murders.

Legal Milestones Overlooked: Brady and Miranda

Chester Weger’s trial occurred before two pivotal Supreme Court decisions that emerged just years after his conviction, decisions that could have significantly impacted his case and potentially prevented the wrongful conviction in the Starved Rock Park murders. In 1963, the Supreme Court delivered its landmark opinion in Brady v. Maryland, 373 U.S. 83 (1963), establishing that prosecutors are obligated to disclose to the defense any exculpatory evidence – evidence that is favorable to the defendant and could potentially prove their innocence. Crucially, at the time of Chester Weger’s trial, prosecutors were not legally bound to disclose such evidence. For instance, had prosecutors possessed evidence pointing to another suspect in the Starved Rock Park murders, they had no legal obligation to share that information with Chester Weger or his defense attorney.

In 1966, the Supreme Court issued its ruling in Miranda v. Arizona, 384 U.S. 436 (1966), mandating that criminal suspects in police custody must be informed of their constitutional rights – specifically, the right to an attorney and the right against self-incrimination – before any police questioning. Had Miranda v. Arizona been the legal standard in 1961, Sheriff’s deputies would have been required to advise Chester of these rights before questioning him. More importantly, had Chester requested legal counsel, the deputies would have been prohibited from interrogating him, potentially preventing the coerced confession in the Starved Rock Park murders case.

Evidence of Innocence: Unraveling the Case Against Weger

Numerous factors cast serious doubt on the validity of Chester’s confession and bolster his claims of innocence in the Starved Rock Park murders. Notably, there is a complete lack of physical evidence directly linking Chester to the brutal crime scene. Furthermore, no witnesses ever placed him at St. Louis Canyon in Starved Rock Park when the murders occurred.

However, compelling physical evidence actually supports Chester’s exoneration. A blond hair found on Frances Murphy’s glove was analyzed by Eastman Kodak and determined to be dissimilar to hair samples from Chester. Black hairs were also discovered in Lillian Oetting’s palm; Chester did not have black hair, ruling out these hairs as his. Despite the collection and analysis of numerous hairs and fibers, this crucial hair evidence was not presented at Chester’s trial for the Starved Rock Park murders. The presence of both blond and black hairs on the victims strongly suggests the involvement of two perpetrators in the Starved Rock Park murders. It is also questionable whether the 5’8” Chester Weger could have overpowered and restrained all three women alone.

Chester passed multiple polygraph examinations in the weeks immediately following the Starved Rock Park murders. The decision to administer yet another polygraph six months later, and the subsequent claim that Chester failed this exam, raise significant skepticism.

Chester’s assertion that his confession was involuntary and coerced is strongly supported by Deputy Sheriff Dummitt’s threat of the electric chair if he did not confess. The threat of capital punishment is a leading cause of false confessions. Moreover, Chester’s confession itself is inherently implausible. He claimed robbery as the motive, yet the women’s jewelry and rings were untouched. His account that one of the women initiated the altercation by attacking him, as stated in the coerced confession, also defies logic.

Decades after Chester Weger’s conviction for the Starved Rock Park murders, a juror admitted to the Tribune in 2016 that she found Weger’s confession “[implausible]” even at the time of the trial. Weger’s current legal team, Andy Hale and Celeste Stack, argue that a case built on such flimsy evidence and a coerced confession would never proceed to trial under today’s legal standards.

Around 1982, a Chicago police officer reported an alleged deathbed confession from an anonymous woman in a hospital. An affidavit detailing this event surfaced in 2006. Sergeant Mark Gibson stated that he visited the woman in the hospital to help her “clear her conscience.” The woman reportedly confessed that “things got out of hand” at a State Park and “they dragged the bodies.” Gibson stated that this confession was abruptly cut short by the woman’s daughter, who claimed her mother was not in her right mind. This incident raises questions about a potential alternative explanation for the Starved Rock Park murders.

Throughout his lengthy incarceration, Chester Weger consistently maintained his innocence. In a 1963 letter to the Chicago Tribune, Weger wrote, “[Now there’s nothing in the world that I needed bad enough to kill for.]” His supporters rallied behind him, creating a “Friends of Chester Weger” Facebook page in 2013, which garnered nearly two thousand followers. In 2016, he reiterated to the Tribune that he would rather die in prison than admit to something he did not do, highlighting his unwavering stance on his innocence in the Starved Rock Park murders case. Despite his continuous fight for exoneration, Weger’s plea for clemency was denied in 2007.

Chester Weger’s Parole and the Ongoing Quest for Exoneration

Chester Weger released from prison, marking a new chapter in the Starved Rock Park murders saga and his fight for exoneration.

Chester Weger released from prison, marking a new chapter in the Starved Rock Park murders saga and his fight for exoneration.

On November 20, 2019, the Illinois Prisoner Review Board, after 23 previous denials, voted 9-4 to grant Chester Weger parole. At the time of his release, Chester Weger was the second-longest-serving inmate in Illinois history, having spent 61 years behind bars for the Starved Rock Park murders. Chester Weger’s attorneys, Andy Hale and Celeste Stack, expressed their delight at Chester’s release and reaffirmed their commitment to continuing his fight to prove his innocence. Lead counsel Hale told ABC7 news, “[We are very pleased that Chester was released today into the arms of his devoted family, who have waited decades for this day.]” The release of Chester Weger marks a significant development in the Starved Rock Park murders case, but for many, the quest for true justice and exoneration remains ongoing.