Many perceive rock climbing as a daredevil sport, a brute test of strength and a risky dance with danger. Popular imagination often paints a picture of adrenaline-fueled screams and raw power. Before experiencing it firsthand, perhaps your mental image, like mine, involved something akin to intense gym workouts mixed with extreme sports bravado. However, the reality of rock climbing is far more nuanced. It’s a pursuit that blends physical exertion with profound intellectual engagement. It’s about deciphering intricate puzzles using both body and mind. Success comes from navigating complex sequences of rock formations through a combination of grace, mindful awareness, strategic thinking, and, yes, strength.

For dedicated climbers, the ultimate aspiration is often the “project” – a challenging climb that demands days, weeks, or even months of dedicated effort. Initially, these projects can appear insurmountable. The handholds might seem impossibly small or awkwardly positioned; the wall might be excessively steep or featureless. Yet, with persistence and focused attention, a solution begins to emerge. Move by move, climbers meticulously analyze and refine a sequence that might just unlock the route. It might involve placing a left foot with pinpoint accuracy, achieving a precarious balance. Perhaps it requires flipping a hand to press against a rock ridge, adopting a body position reminiscent of a yoga triangle pose to gain reach. Then, extending a right hand to grasp a minuscule pocket in the rock face. Followed by a high step and another hand flip within the pocket, shifting body weight to progress further. Through meticulous practice and unwavering focus, the seemingly impossible gradually transforms into the attainable. The holds become familiar, the movements ingrained. Climbers learn when to unleash maximum effort and when to conserve energy. The body adapts and strengthens. Finally, the day arrives when everything clicks, and the climber ascends the wall in a fluid, almost dance-like manner.

rock climbing aesthetics 2

rock climbing aesthetics 2

Dance serves as an insightful starting point for understanding the aesthetic dimension inherent in Rock Climbing And its appeal. Climbing, like dance, offers not only physical challenge but also profound aesthetic rewards. Listen to climbers discuss their experiences, and you’ll notice a striking similarity in their language to that of dancers. They speak of climbs with “beautiful movement,” “good flow,” and “interesting sequences.” They differentiate between “ugly climbs,” “elegant climbs,” and even “gross climbs.” Initially, one might assume they are simply describing the visual appeal of the rock itself. And indeed, climbers appreciate aesthetically pleasing rock formations – a clean, continuous crack in a smooth face or a dramatically jutting fin of rock. However, delve deeper into a climber’s explanation of a climb’s beauty, observing their gestures as they reenact the precise, often unusual movements – arms extended, legs mimicking positions in the air – and you realize their primary focus is the quality of movement itself. It’s about the sensory experience of interacting with the rock, the exquisite sensations within the body, and the intense mental focus required.

Philosopher Barbara Montero, specializing in the philosophy of dance, compellingly argues that the core aesthetic experience of dance lies in a dancer’s proprioceptive awareness – the sense of moving through space and perceiving that movement as beautiful. Our appreciation of dance isn’t solely visual; we experience it viscerally, in our muscles and neural pathways. Consequently, Montero suggests that dancers themselves, and audience members with dance experience who can mentally embody the movements, are best positioned to understand the aesthetics of dance. The beauty of dance, therefore, is fundamentally a beauty of embodied movement.

Reflecting on my own most cherished climbing experiences, the most vivid memories are the sensations of movement – the feeling of grace, the ability to move with precision, economy, and elegance. This quality of movement is something I savor, revisit in daydreams, and that ultimately draws me back to the rock. Often, this movement quality is amplified when intertwined with challenging situations. Some of the most unforgettable climbing moments are those where exhaustion was setting in, perhaps with minor scrapes and raw fingertips. In these moments, quieting the mind, calming the breath, and pushing through physical limitations allows one to access an inner reserve of elegance and precision, discovering a remarkable quality of movement even under duress.

Climbing shares similarities with dance, yet it is not merely dance. Rock climbing involves graceful movement that is consistently directed towards a specific, task-oriented goal: reaching the summit. Often, the greater the challenge of the ascent, the more rewarding the experience. Climbs not only permit graceful movement; they sometimes demand it. Careless movements are punished; climbers are ejected from the rock face. The efficient movement in climbing emerges as a direct response to a very specific set of constraints dictated by the rock. Whether on natural rock or an artificial wall, the structure dictates potential sequences of movement, but it doesn’t prescribe the exact choreography, unlike dance where a choreographer often sets specific steps. In climbing, the movement sequence is invented, improvised in response to the unique problem presented by the rock. While observing and learning from other climbers’ techniques is valuable, ultimately, each climber must adapt those movements to their own body and style. Imitation is a starting point, followed by adaptation and refinement, guided by the challenges posed by the rock. Fundamentally, climbing is a puzzle-solving activity. Movements are always reactions to the obstacles presented by the rock. The elegance achieved is born from the necessity of efficiency, of conserving precious stamina.

Rock climbing, in essence, is a game. Here, philosophy, particularly the work of Bernard Suits, provides further insightful perspective. Suits’ book, The Grasshopper: Games, Life, and Utopia, offers a delightful and often overlooked exploration of the philosophy of games. It reimagines the classic fable of the grasshopper and the ant. Traditionally, the grasshopper, idle throughout summer, perishes in winter while the industrious ant thrives. The conventional moral: hard work is essential for survival. Suits subverts this moral, presenting the grasshopper as a hero, an exemplar of the playful spirit. The book begins in a charmingly Socratic style, with the Grasshopper, the philosophical champion of play, on his deathbed, surrounded by devoted disciples. He is starving, having steadfastly refused to work. His followers plead with him to accept food, to allow them to work and provide for him. But the Grasshopper refuses, declaring that accepting their help would turn them into ants, and doubly so! He would rather die upholding his commitment to idleness!

The Grasshopper then presents his disciples with a series of riddles about play and games before passing away. The remainder of the book follows the disciples as they grapple with these puzzles, ultimately arriving at a definition of “game,” directly addressing Wittgenstein’s challenge that many terms, especially “game,” resist rigorous definition. Suits offers several versions of his definition, with the most accessible, “portable” version stating:

“Playing a game is the voluntary attempt to overcome unnecessary obstacles.”

This definition is remarkably broad, encompassing board games, sports, rock climbing, and even certain academic pursuits. Suits’ definition has become influential, and sometimes controversial, in academic circles studying games.

The full version of Suits’ definition clarifies that games involve adopting artificial goals and intentionally imposing inefficient means to achieve them, all to create a distinct type of activity. The objective in basketball isn’t simply to put the ball through the hoop – this action holds no inherent value in itself. If it did, we could simply use a ladder to place the ball in the hoop at our leisure. Instead, we embrace the artificial goal of shooting hoops and accept the imposed barriers – opponents, dribbling rules – to generate the engaging activity of playing basketball. Crucially, game-playing is defined not by the physical actions themselves, but by the player’s intentional stance toward those actions. In essence, in ordinary practical activities, we employ means to achieve independently valuable ends. However, in game activities, we adopt artificial ends precisely to engage in the chosen means.

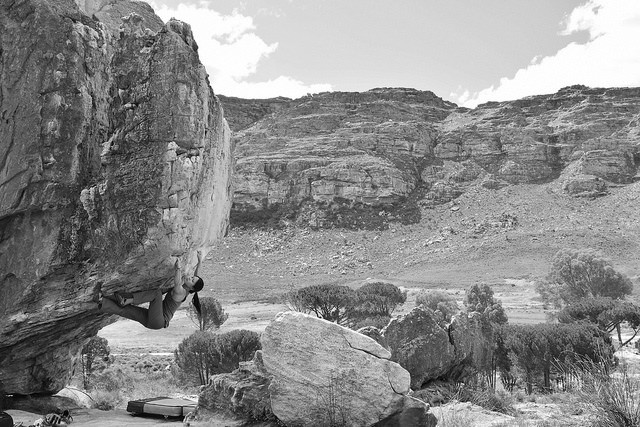

Returning to rock climbing, my preferred discipline is bouldering – climbing without ropes on short rock formations, typically under twenty feet, using crash pads for safety. Bouldering originated as a training method for longer, roped climbs, but quickly evolved into a distinct pursuit valued for its own merits. Boulderers often refer to specific climbs as “boulder problems,” explicitly drawing a parallel to chess problems. Boulder problems are frequently short, incredibly challenging, and involve repeated attempts and falls before success is achieved. If multi-day roped ascents of cliffs are the marathon adventures of rock climbing, bouldering is the sprint.

Suits himself uses mountain climbing as an example of a game. The objective isn’t simply reaching the summit; after all, one could reach the top of Everest by helicopter or ascend El Capitan via the road on its backside. The essence of the game lies in achieving the summit using a specific, constrained set of means – climbing. This is undeniably true in bouldering. A common experience for boulderers: while intensely focused on a difficult overhanging face, a child might casually walk up the easier backside of the boulder and look down, gleefully pointing out the “easy way up.” While the temptation to explain Suitsian game theory to them is sometimes strong, usually, especially on a day off from academic duties, the preferred response is to simply relax and enjoy a post-climb beer.

Thus, climbing fits Suits’ definition of a game. However, it’s a particularly intriguing type of game, embraced by many for overtly aesthetic reasons. In the philosophy of sport, Suitsian analysis is prevalent, yet discussions often narrow the motivations for engaging in such games to skill development, physical excellence, or competition. Suits’ framework, however, allows for any motivation to initiate a game activity. Listening to climbers reveals that aesthetic motivations, particularly proprioceptive aesthetics, are frequently central to their passion.

Consider The Angler, a classic boulder problem in Joe’s Valley, Utah, revered in one of bouldering’s most beloved regions. Interestingly, watching someone climb The Angler is not visually captivating, especially for non-climbers who often prefer watching explosive, dynamic movements – like those seen in climbing competitions with large jumps between holds. The Angler is characterized by slow, deliberate, and meticulous movements. Experienced climbers appreciate subtle, intricate movement, but even then, visible movement is more engaging – re-balancing, yoga-like stretches, distinct body postures. The Angler lacks visible dynamism. It’s a gradual, delicate climb involving a sloping, slippery ridge for handholds and tiny, almost imperceptible footholds. Success hinges on minute shifts in balance, maintaining core tension, and painstakingly adjusting the center of gravity. When executed correctly, it feels exceptional – a sensation of becoming pure precision, a scalpel of delicate movement ascending the rock. Yet, to an outside observer, it appears… unremarkable. Even experienced climbers might find watching someone else on The Angler quickly boring. Despite my deep appreciation for The Angler, I confess to having sat beside it with a beer, attempting to watch others climb, only to lose interest almost immediately. In this climb, the captivating internal movements are invisible to the external eye. The aesthetics of movement here are solely for the climber’s personal experience.

rock climbing aesthetics 1

rock climbing aesthetics 1

The Angler exemplifies a perfect boulder problem in many climbers’ eyes. It possesses all the desirable qualities. The rock itself is strikingly beautiful. Crucially, what climbers term “the line” – the intended path up the rock – is visually appealing. The feature followed is distinctive, and the climb’s trajectory is both clear and aesthetically pleasing. The movement sequence is wonderfully engaging. Best of all, these elements harmonize beautifully. In The Angler, the movement quality evolves throughout the climb. Initially intricate and subtle, the movements become bolder and more exposed higher up and to the right. Seasonally, the final moves – bold yet relatively straightforward – are made directly above the river. The sensation of movement intensifies as the climb progresses, transitioning from delicate to exhilarating. Rock, line, and movement achieve a remarkable consonance. Reaching the top after sustained effort and focused attention, face inches from the rock, searching for minute friction points, climbers transition into a river canyon, surrounded by flowing water, wind, and the sound of the river. The feeling of accomplishment merges with the sensation of wild, open nature.

While philosophical work demands focus, the level of concentration I’ve experienced on challenging climbs is unparalleled. Mind intensely focused on subtle rock textures for foot placement, ankle angle precision, maximizing grip with handholds, and the precise force needed for each foot movement. One might superficially assume, within a traditional aesthetic framework, that climbing is merely a technique, a method to focus the mind on external beauty – the rock and nature. However, this overlooks the core experience of climbers. They are deeply attuned to their own movements, appreciating how these movements solve the puzzle of the rock. The aesthetics of climbing are primarily an aesthetics of the climber’s own motion and the elegance with which that motion functions as a solution to a problem. For the climber, a unique harmony emerges – a harmony between personal abilities and the challenges encountered.

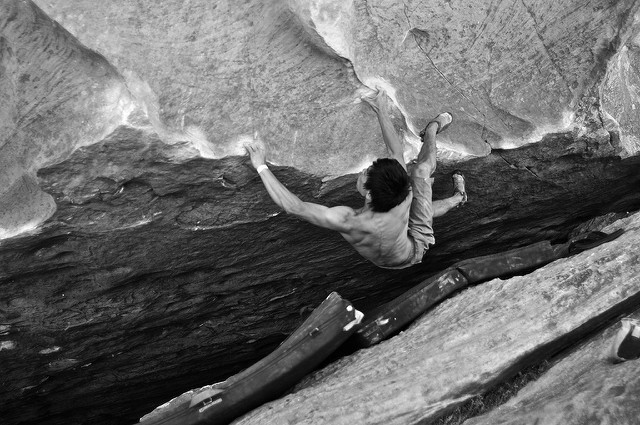

I recall an afternoon spent in the Buttermilks, a stunning bouldering area in Bishop, California. I was intensely focused on a perplexing problem involving heel-hooks, toe-hooks, and inverted body positions. Nearby, a more accomplished climber tackled a far more demanding problem on the same boulder. We spent the entire afternoon absorbed in our respective challenges. He was completely immersed, screaming with effort, cursing playfully, and aggressively engaging with the rock. The crux move involved reaching a poor, sloping hold with his right hand, high-stepping his left foot almost to his chest, and then squeezing himself upward between hand and foot, propelling himself like a watermelon seed to reach a tiny set of pocket holds with his left hand. This move is typical of high-level bouldering – the target hold is so distant that a dynamic, jump-like movement is essential. Yet, the hold is so fragile that any excess momentum risks ripping the climber off the rock.

He attempted this move repeatedly for hours, interspersed with long rests. Frustration mounted, punctuated by curses and near-meltdowns. Finally, with a tremendous, guttural scream, he executed the move. He carried a bit too much momentum, but he instinctively grabbed the next hold with exceptional force, muscles straining, yanking himself back into position, yelling. He completed the problem and descended, staring at his fingertips. One was bleeding.

“Nice job,” I offered. I raised my hand for a high five, but he shook his head, dejected.

“That was ugly as hell,” he muttered. “Terrible style.” He taped his finger, rested briefly, then stepped back up and repeated the climb. This time, it was flawless – a subtle shift, a delicate step, and he flowed through the move effortlessly.

He climbed down, jogged over to me, beaming. “God, what a gorgeous problem!” he exclaimed. “You have to try it. That move is so beautiful. It’s just…” He mimed the move, again and again, “Just fantastic! You’ve got to do it!”

Regrettably, I admitted, the problem was far beyond my current ability.

He shifted from foot to foot, grinning, attempting to feign sympathy. Then, he walked back and climbed it again.

C. Thi Nguyen is assistant professor of philosophy at Utah Valley University, working in epistemology, aesthetics, and games. This piece draws from a work in progress.

Top image: Dana Le/FlickrBottom image: Simon Li/Flickr